|

|

Hyperlocalism seeks to bridge the physical/digital divide by focusing on the use of information to create technology tools and media oriented around a well-defined area and inspired by the needs of local residents. Maps and mesh networks are tools that can be particularly leveraged to enable hyperlocal connectivity and information flow; I’ll briefly unpack the latter (mesh) and then demonstrate the possibilities for hyperlocal mapping.

510pen as conceptualized by Mark Burdett is based on the principles of the Open Wireless Movement: that by sharing our wifi with our neighbors, we contribute to increasing access to the internet while simultaneously creating more positive relationships with our local communities. This premise is clearly the most obvious benefit of mesh networking and is enthusiastically supported by the folks I’ve been talking with in Oakland, who see the lack of widespread internet access in their neighborhoods as a very present and real issue.

Then there is the application layer – which is the level at which TidePools is working to create software for hyperlocal neighborhood mapping. Beyond internet access, a resilient communications network endeavors to create point-to-point networks that mesh the barriers between physical and virtual space. What kinds of data and landmarks define the available resources and value of a physical community?

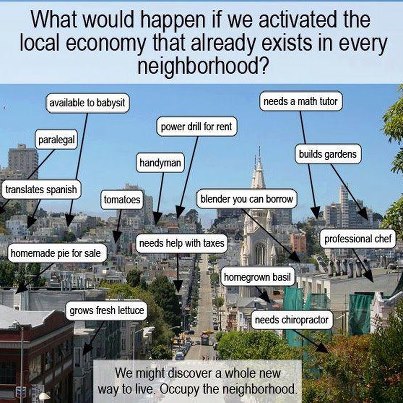

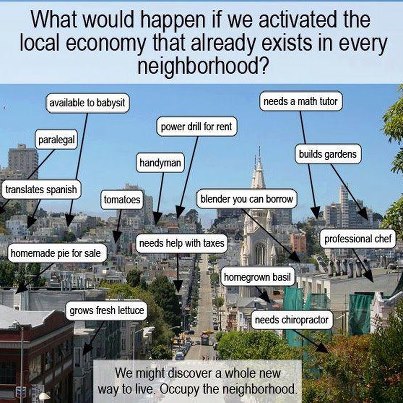

It might look something like this:

…in which the skills and resources of your neighbors are made visible and available to others on the local network.

Or perhaps like this, visualizing the history of a neighborhood through a timeline-based photographic montage:

Alternatively, we could use hyperlocal mapping to depict a more realistic sense of the cultural characteristics of various neighborhoods, rather than the oft-arbitrary borders drawn by state governments:

As I continue interviewing and chatting with folks about things they’d love to see on local maps, a few themes have emerged:

Environmental activists seeking to visualize pollution data, park locations, local wildlife, etc;

Unemployed and homeless folks seeking to map out resources such as public computers, food kitchens, excellent dumpsters for food foraging, and crisis centers for various demographics.

Long-term residents wishing to map out and connect local businesses and organizations in their neighborhoods.

Community organizers interested in mapping their community to strengthen awareness of existing resources and publicly accessible spaces.

Hackers and techies interested in creating decentralized networks and alternative telecommunications (eg; mesh networks, low-bandwidth software radios, etc;) – which necessarily requires mapping line-of-sight on rooftops and potential barriers to connectivity (such as raised highways)

Open government folks mapping open civic data such as crime, foreclosed / blighted properties, city legislative initiatives, and historical information.

Here are some projects I’ve been working on with some other hard-working, socially-conscious people that are tackling these needs:

Tidepools – Hyperlocal neighborhood mapping software.

510pen (Five One Open) – Creating an East Bay mesh network.

Open Oakland – Volunteers mapping out open civic data in Oakland.

OpenOakland Digital Divide – Mapping out existing Oakland efforts addressing the issue of access to technology.

Oakland Wiki – A site all about Oakland, with over 2,000 articles written by community members.

Mycelia – A decentralized database I’m working on with my partner for mapping tools/inventory, skills, and projects between and among hackerspaces, intentional communities, and other self-organizing spaces.

I welcome and encourage further suggestions and use cases in the comments below!

Among technologists, for whom information and communication flow at hyper-speed and social bonds are increasingly interest-based, developing relationships with people and communities outside of your comfort zone of easy compatibility can feel frustratingly slow. The world of software development does not typically attend to the kind of bottom-up, community-based research process I’m accustomed to as an anthropologist – rather, rapid iteration is prized over emergent design and humans (who have a tendency to wield tools in unexpected and surprising ways) are reconfigured as ‘users’ of software that provides a ‘service.’ What follows is an attempt to articulate the process of doing anthropological research for developing technological tools, in the hopes of inspiring technologists to rethink the process of software development in a more human, culturally accountable manner.

Ethnographic research is the art and science of becoming attuned to the cadence of a culture. Largely, this entails the anthropologist’s direct engagement in a cultural milieu, the everyday observations of which are recorded as field notes. Field notes based on the anthropologist’s observations are accompanied by semi-structured interviews (typically recorded, transcribed, and coded) and occasionally surveys to incorporate the variety of roles, activities and perspectives that make up the cultural phenomena under study. An ethnography tells the story of a cultural group – incorporating field notes, interviews, historical research and critical analysis – and is the product of field research that relies on participant-observation as the principal methodological approach. Recent developments in the field of anthropology explore and experiment with new techniques for writing the ‘other’ that often entail treating the self as an other, first and foremost. Reflexivity is crucial for engaging in critical thinking about one’s own role and bias in cultivating cross-cultural understanding.

Multiple methods of analysis are employed in order to understand the complex dynamics of building technological tools for communities from the ground up. Semi-structured interviews are a primary source of the data and information gathered in the process of building tools responsive to community needs. Personal interviews allow community members to voice their opinions and share their biographies in a safe space of confidentiality and empathic listening, while group interviews encourage collaborative storytelling about the community’s origins and history, present issues and projects, and reveal collective visions and goals (as well as anxieties and fears). Focused discussions with community members are also a primary planning and implementation space, including sit-down brainstorming sessions aimed at raising issues and needs that could be addressed by the project.

Of further relevance is what’s known as Community-Based Participatory Action Research. Community-based participatory action research is a methodology that reorients authority horizontally. That is to say, the final product of community-based research is designed to facilitate alliances between local organizations that have vested interests in the community under study, rather than research designed to fulfill an institutional, governmental or corporate agenda. As such, community-based research tends to blend academic and activist agendas, ultimately producing something of value to the research “subjects” that is at once collaborative and politicized.

Always a fan of mixed methods, I’ve been working with the Open Oakland Digital Divide group to reach out to organizations that are already addressing access to technology in Oakland. Rather than reinventing the wheel, we thought it prudent to endeavor toward creating a hub of existing efforts by researching and documenting them on OaklandWiki. Providing such a service ideally demonstrates to the groups we’re reaching out to that we respect and appreciate the work they’ve been doing, enabling us to more effectively request their time for visiting and asking questions about what they need that we could potentially provide. It furthermore creates an opportunity for us to serve as bridges, building a coalition of those committed to addressing the digital divide by making them visible to each other.

The purpose of this post was not in any way intended to condemn the culture of open source communities. The collaborative research process of the Digital Divide group embodies the DIWO (Do It With Others) ethos that I so dearly adore about hacker culture – though it’s doubtful that many members of the group self-identify as hackers. Tidepools, the open source neighborhood mapping project I’ve been working on, was developed under the direct input of the Red Hook community through a unique hybridization of technological development rooted in ethnographic process. I’ve become ever more passionate about the intersections between cultures, the power and potential of fusing worlds. That excitement and fervor has found me racing between spaces, places, communities and meetings – constantly in action, constantly iterating an idea into refinement without allowing it to grow. Borrowing from the best of both open source culture and anthropology, I’m committing this blog to being a living testimony to transparent documentation, reflexivity and critical thinking – but for that to happen, I have to learn to slow down and allow thought to crystallize into language. Here’s to slow dev! 😉

As I launch into week 5 of my work with the Open Technology Institute, I’ve begun to collaborate with a variety of groups, organizations and actors who constitute part of the emerging network of activity around developing community mesh networks and mapping applications in Oakland, California. The idea is to facilitate the grassroots (bottom-up) development of community mesh and mapping initiatives already ongoing in the East Bay, while playing a supporting role in documenting progress and connecting communities of interest.

sudo room is a young hackerspace in uptown Oakland dedicated to transparency, social justice and the creative application of technology. Sudo room is an open, inclusive space for free education and access to tools, as well as a venue for hosting local civic hacking, technology and learning initiatives. The groups and projects detailed below meet at and work regularly out of sudo room, which serves as an ongoing hub for events ranging from 72-hour hackathons to meetings between city projects and local hackers.

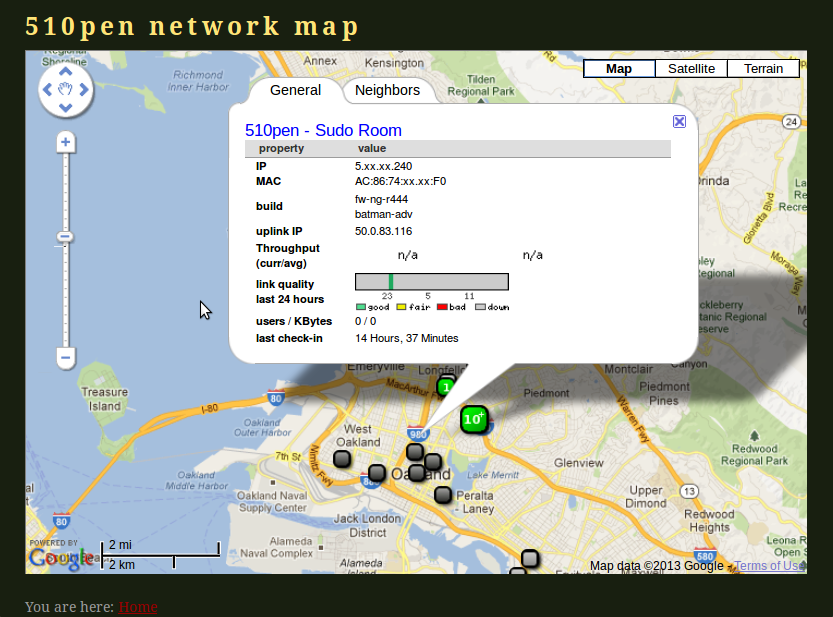

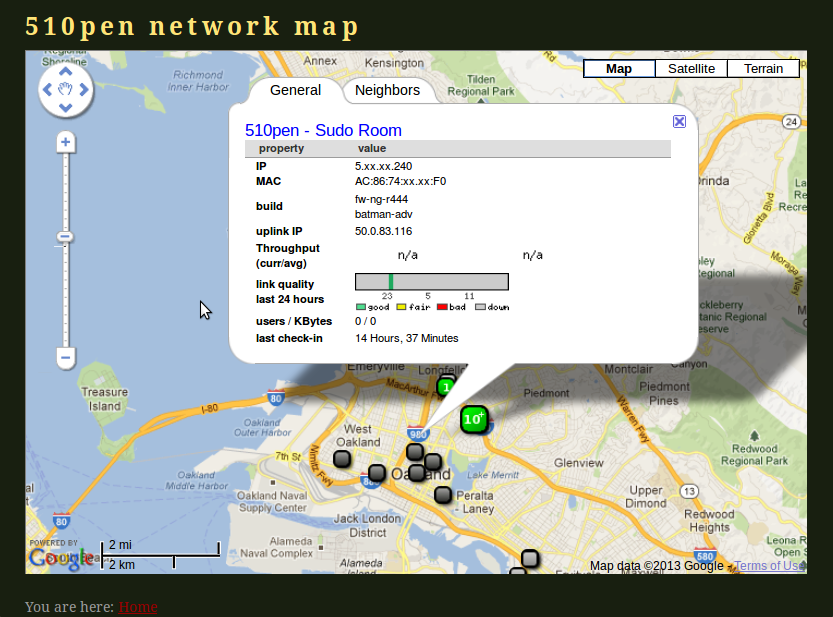

510pen Network Map, with currently-inactive sudo room node information displayed. 510pen is an East Bay community mesh network started by Mark Burdett in 2009. Currently, most of the nodes that were set up between 2009 and 2011 are inactive and in need of tech support. As of last week, we’ve begun meeting weekly at sudo room to discuss basic hows and whys of community mesh networks; wireless network hardware and software; how various community wireless efforts can cooperate and collaborate; models for organic growth, organization, support and sustainability; and how we can join forces with local residents, small businesses, non-profits, municipalities and anyone else to build a ubiquitous community mesh network.

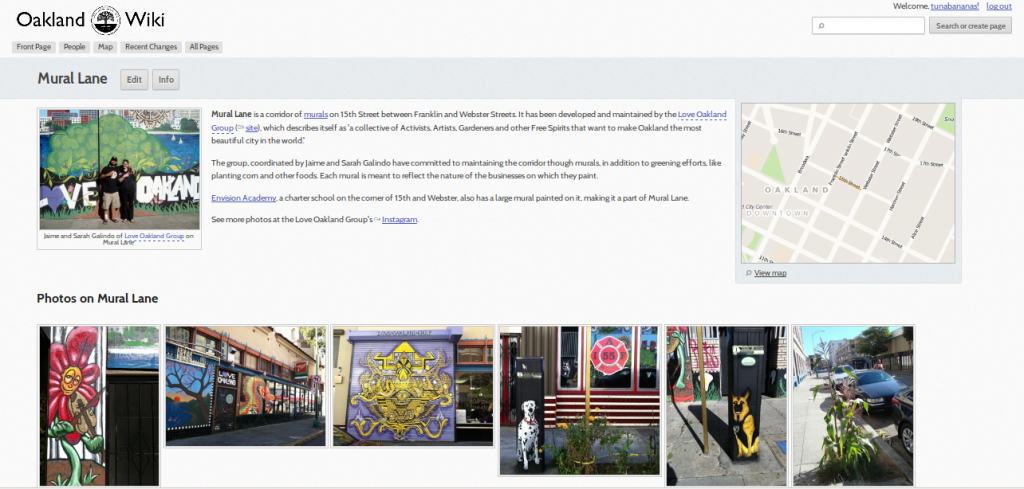

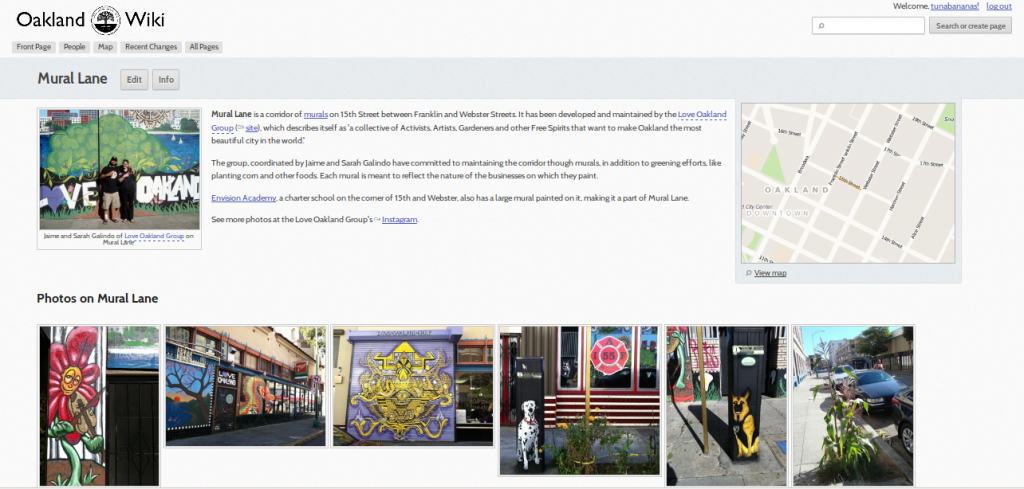

Oakland Wiki is a LocalWiki repository for documenting the infrastructure, communities, and history of Oakland. Oakland Wiki hosts weekly edit-a-thons at the Oakland History Museum, where older residents / historians meet with the Oakland Wiki team to document the history of Oakland. Oakland Wiki is also hosting a civic data session at Open Data Day on February 23rd. The goal of this session is to provide a qualitative focus to an otherwise quantitatively-focused event, encouraging the contribution of information about city council, city policies, politics, and key figures in the city – essentially creating narratives around the past, present, and future of the city in an accessible and historically-rich manner.

Oakland Wiki: Mural Lane The Open Oakland Digital Divide Group is a collaborative effort to coordinate the various organizations and individuals working on digital divide issues in Oakland. Spawned out of a session at CityCamp Oakland last December, the group consists of local citizens, technologists, and community change workers interested in creating solutions for effectively addressing the digital divide in Oakland. At our first meeting, held on January 24th, we articulated a few tangible goals to work on: individually reaching out to preexisting groups addressing digital divide issues to assess their needs and available resources; group field trips, visiting for instance a local swap meet where broken computers are donated to a group that turns them into working machines; and creating a central directory of digital divide resources for the city, including for instance a map of local, free tech meetups.

These are just a few of the most prominent players and projects as we move forward in developing relationships with community organizations and neighborhood groups. I will continue to transparently document my ongoing research progress at the Tidepools Wiki, and welcome your comments and contributions in the comments of this post!

Last month, I spent several days staying with some friends in Brooklyn, New York who’ve been working full-time with Occupy Sandy‘s relief/rebuild efforts. While the devastation wrought by Hurricane Sandy has been heartbreaking and the lack of federal response infuriating, the kind of connectivity and mutual aid that has emerged in the resulting months is nothing short of inspirational. And profoundly educational.

Here are the meeting minutes from the network-wide Occupy Sandy meeting I attended right before the December solstice. It was the most well-facilitated meeting I’ve ever participated in, with the focus primarily being upon sharing updates from representatives of the disparate groups organizing Sandy relief efforts in the Far Rockaways, Red Hook, Coney Island, Staten Island, Long Island, and beyond. As Christmas was approaching, the core issue revolved around the many thousands still without heat or electricity. In the Far Rockaways, over 20,000 residents were still without power as freezing temperatures approached. FEMA, overwhelmed and underprepared, had all but handed over its limited resources to the Occupy Sandy camps that had popped up within days of the superstorm. Only this week – more than 75 days after the storm – did Congress approve a bill to send long-overdue federal aid to Sandy victims.

Occupy Sandy, the central hub of which was the amazing Church of St. Luke and St. Matthew (pictured above) in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, sprung to work less than 48 hours after the storm. Tens of thousands of volunteers have since coordinated donations, trained new volunteers, cooked meals for masses of people, scraped mold off of buildings and homes, and assisted residents in completing the paperwork needed for securing governmental aid and navigating insurance claims. There is still a good deal of work to be done to rebuild the neighborhoods destroyed by Sandy, instilling in me a resurgence of passion to develop human and communications infrastructure in preparation for the kinds of crises that can arise when the infrastructure we typically depend upon falls apart.

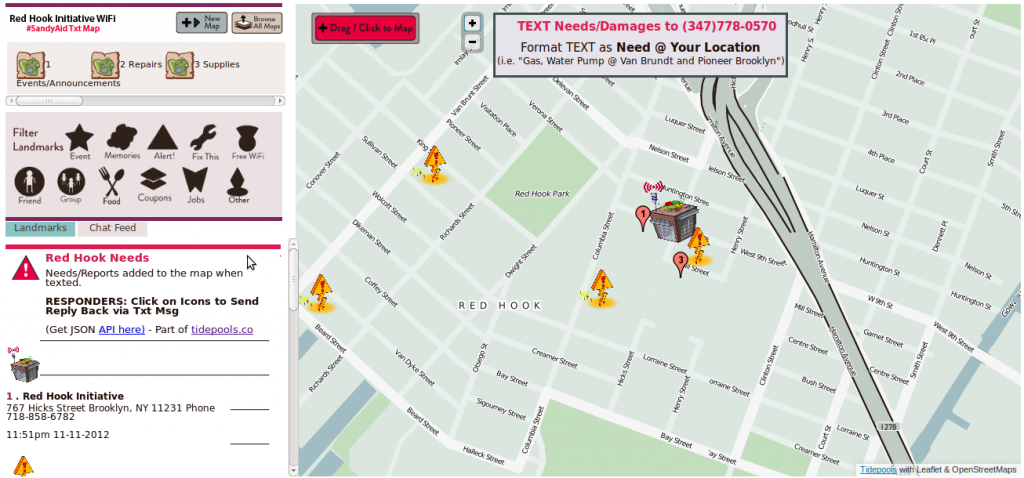

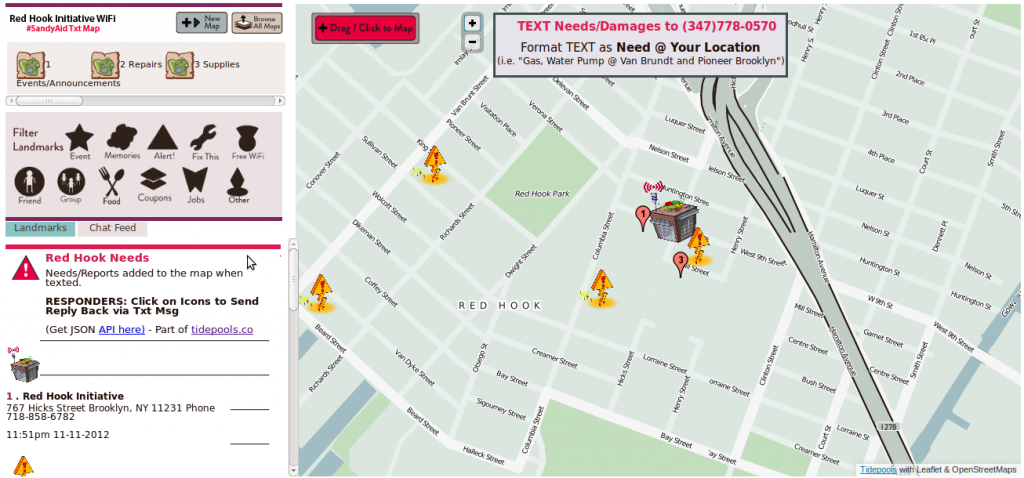

My experiences in New York were concomitant with the exciting news that I’d been accepted for an internship with the Open Technology Institute sponsored by GNOME’s FOSS (Free and Open Source Software) Outreach Program for Women. Specifically, I’ve been tasked with the work of designing use cases for community wireless mesh network applications such as TidePools, a neighborhood mobile mapping platform. TidePools was designed around the particular needs of residents in the Red Hook district of Brooklyn: reporting civic issues such as broken street signs; adding nicknames for the areas around the neighborhood; sharing information about local events; and creating an alert system for the often-spotty public transportation schedules. The potential uses of the platform are too numerous to mention and very much contingent on local context.

Post-Sandy, a TidePools node (pictures above) was deployed for mapping out local needs, sent by residents and volunteers via SMS text messaging for use by first responders seeking up-to-date information on where supplies such as food, water, gas and generators were needed.

You can learn more about my ongoing work for the Open Technology Institute by stopping by the TidePools wiki, where I’m collating ideas, use cases and research surrounding community mesh networking and mapping applications. I’ll also be blogging regularly about mesh applications here, focusing on stories that demonstrate how we can use this technology to facilitate coordination and communication in our local communities. For the latest updates on the Occupy Sandy relief efforts, please visit the online hub at InterOccupy.net.

|

|