Below are crib notes from my 4th American Anthropological Association meeting. Enjoy!

——

I’d like to begin by putting my story right on the table: I’m an anthropologist without an academy – a decision I made halfway through my Ph.D program for a variety of reasons that could be clustered under a personal inability to be complicit in a system that financially exploits young people for the purposes of paying off its debts to Wall Street.

Six months before Occupy began, I took my first leave of absence from my program, having befriended a group of wonderfully weird, idealistic brains up in the Bay Area. They were all super active at Noisebridge, a hackerspace in the mission open to the public. We were working on creating a live/work hackerspace in Oakland when I got pulled into working on OccupySF’s website at Noisebridge. I took my second leave of absence in the fall, swept headlong down the rabbit hole of revolutionary fervor.

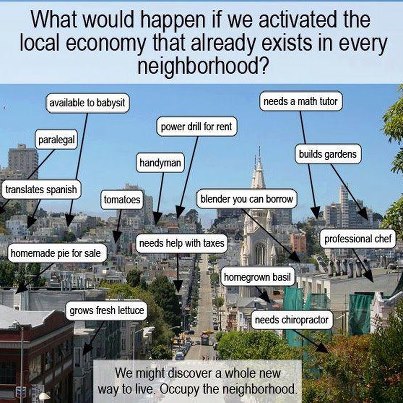

Hackers and academics share a common challenge in contemporary culture: walled gardens. While internet freedom fighters rally against the walled gardens of Google and Facebook, activist-academics fight similar battles over the literal walled gardens of the Ivory tower and closed-access journals. From my vantage point, the solutions are the same in both instances: creating decentralized networks devoted to self-sufficiency, autonomous learning and grassroots, DIY community-building – making the very blueprints for such endeavors open source, aka freely available to the public.

To rewind a bit and cover any confusion over the oft-misunderstood term “hacker,” allow me to clarify: A hacker is not necessarily someone who maliciously breaks into computer systems – as mass media portrayals would have you assume. A hacker is a learning enthusiast, someone who is so curious as to take something apart completely in order to discover the fundamental components of a system. To “hack,” then, is to learn the process of creating something through doing it, and through modifying it to do what you want it to do. Put simply, in the words of McKenzie Wark (author of The Hacker Manifesto): “The slogan of the hacker class is not the workers of the world united, but the workings of the world untied.”

What I’m proposing, then, is “hackademia”. Hackerspaces and Occupy, like anthropology has always done, have created bridges for moving between worlds. It’s my adamant belief that the role of an anthropologist is simply that of storyteller. The very best we can do is transmute the mundane and otherwise hidden into vibrant and visible poetry; the worst we can do is keep our stories contained from those who have ears to hear.

So last night, I’m at the weekly meeting for the Oakland hackerspace I’ve been co-creating with a hodgepodge array of changemakers for the past year. I’d sent a callout for a ‘meta-organizational hacking’ meetup to take place an hour before the regular meeting. The goal was to identify where we could possibly refine our process, assisted by a Danish Kaos Pilot (the Kaos Pilots being a program focused around social entrepreneurship and leadership).

[SHOW SOME SLIDEZ]

This month marks the one-year anniversary of Sudo Room’s first meeting. Drawing from prior experience as well as the Hackerspace Design Patterns guide, we set up a mailing list, wiki, and IRC channel. We take notes together using an etherpad shared document, and post them on the wiki after each meeting. We decided to run by consensus without fastening ourselves to a binding agreement; iteration is invaluable, and we wanted to leave room for growth and change.

As a subculture, or even a ‘class’ according to Wark, hackers are remarkably meta-aware. Rather than genetic reproduction, hacker culture reproduces itself memetically. The hacker ethos of open source collaboration provides a roadmap, replete with tools for multi-maker storytelling. Our dedication to “copy / paste culture” means we have been committed from the first to the active practice of openness, transparency and collaboration – making this community an ideal laboratory for experiments in collaborative ethnography and multimedia storytelling. No confidentiality agreements needed when everyone is down to open source all the things!

While Sudo Room embraces an inclusive model of “hacking” that goes beyond hardware and software – to wetware, wearables, and even culture itself – there is certainly reason to resist confining ourselves to hacker culture alone. While not disregarding the admirable ethical core of lifelong learning, decentralization, and collaboration, the term is also connotative of an elite culture consisting of a privileged class of internet savants.

So I started hanging out in the #geekfeminism channel on IRC to get feedback on how we could create a more inclusive space. In turn, some geeky feminists started hanging out in the #sudoroom channel and contributing to some of the truly epic conversations we’ve been having around access and diversity.

There is something truly exciting about the interconnections between subcultures and the value of their hybridization in the spirit of creativity. What happens, for instance, when you combine botany buffs and hackers? You might get something like BioBridge, the amorphous DIYbio contingent of Noisebridgers, working on experiments in oyster mushroom growing and developing Arduino-controlled sensors for monitoring temperature and pH levels in kombucha brews and sourdough starters. Here you would also find overlap with Tastebridge’s Vegan Hackers night and perhaps some friendly Food Not Bombs volunteers.

While ‘collaborative ethnography’ as a form of ethnographic co-representation is not new – the idea was introduced in Writing Culture well before the turn of the millenium – the current milieu of rapid technological progress combined with what appears to be an earnest and timely revival of the commons is well-positioned for new experimental approaches to co-creating ethnography.

As resident cyberanthropologist (or, as others have called me, “that anthropologist who went rogue”), I find my skills uniquely situated to the task of creating replicable, transparent documentation, facilitating cross-cultural communication (particularly with groups representing marginalized voices), and providing meta-analysis of the culture we’re creating.

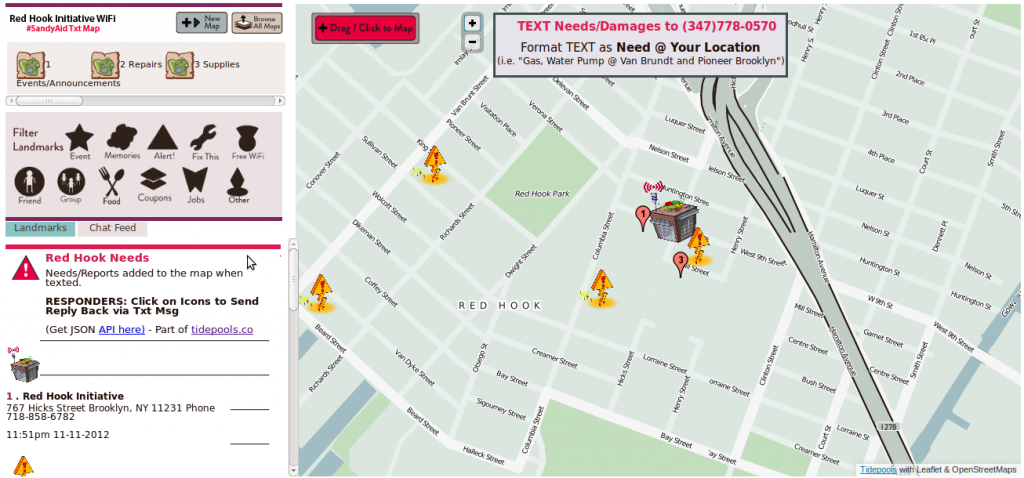

Some of these projects include:

-IRC bot, which anyone can contribute to, that logs channel conversations and enables bookmarking by participants in the chat.

-Autodocumentation Stations established in hackerspaces across the globe

-Connecting maker culture through a decentralized network of nodes denoting places, people, tools, projects, and blueprints.

One year ago, I stood up on a podium much like this one, making a callout to all the anthropologists present to take themselves down to the Occupy Montreal camp two blocks away from the posh convention center in which the AAAs were happening – closed to those without tickets costing somewhere between $200 and $500 – and to share their knowledge through outdoor teach-ins.

A lot has happened since that fateful weekend when I found myself more excited and welcome out there, sharing stories with haggard, weary occupiers, rolling cigarettes in the blustery wind not even thinking about just how cold my fingertips were. I remember walking through the publishing hall afterwards, in the polished corridors of the convention center, and being angry at how much everything cost, how it all just goes to the publishing companies anyway, how inadequate academia’s response has been to the liberation of information enabled by the internet and its dogged defenders

My aim in this talk is to illuminate a kind of “posthuman ethnography” that incorporates multimedia archives and community documents, the social organization of networked space, web-based communication tools and collaborative projects alongside the stories and shared experiences of individual members. In this sense, the end “product” is as collaborative, dynamic and diverse as its subject.