|

|

“The city is not a concrete jungle, it’s a human zoo.”

Desmond Morris, The Human Zoo.

Soaking up the sunshine this weekend, I perched with a friend on the steps of Union Square. Nearby, a group of attractive young white kids with brightly colored hair spun poi and hula-hooped in fashionable earthy garb, crafting a performative stage at the foot of the steps where dozens of people sat. I watched and wondered, as I always do, at the seemingly innate enjoyment of judging gazes, small envies, unsubtle desires, attentive eyes consuming their brightly colored shimmying hips and tanned, fluid limbs. I’m at a loss for how to go about reclaiming a lifestyle co-opted by childish style tribes, recuperated and sold back in the tone of the “underground.” But as Kurt Vonnegut says, so it goes…

A man holding a sign ranted loudly about the perils of nanotechnology, drawing a small cluster of avid listeners. My friend attended to her Seed Magazine, which highlighted the contemporary debate on the issue. She commented on the young man giving out free hugs while simultaneously strutting about in a shirt emblazoned with the words “made of poison.”

I casually struck up a conversation with the man chillin’ to my left, complimenting the intricate detail of the colorful psychedelic prints splayed out around him. Averting his eyes, he described his process as one of “adding to” pre-existing images – at this, I raised an eyebrow and smirked at the psychedelic elephant in my hands. Smoothly, he then pulled out a translucent pair of prints and moved them slowly across one another, blurring and goo-ifying a gigantic block print of the year 2012. Wince.

Gradually, we inserted ourselves into another nearby spectacle that had drawn a dense crowd- two lithe black men dressed in bright, skin-tight animal print bodysuits engaged in a wildly contortionist dance, bizarre twistings of bodily form. For their grand finale, one leapt effortlessly over the heads of half a dozen “volunteers.” Throughout, they called for the audience to give money for their endeavors, and at the end passed three large buckets around. Embarrassed, I avoided the buckets, reaching a hand into my pocket to ensure my four dollar bills were still milling about.

The area where I run at the Chelsea Piers has finally finished construction (or at least a substantial portion of it), and is now allowing people to meander along the shiny new walkways accented by bright green grass and surrounded by trees and water. It is beautiful!

Tonight, I rambled to the corner market for a beer. It was around midnight, and I found myself gazing in at the bars closing down. Bartenders, cooks and barbacks gathered in small pockets just beyond accessibility, cocooned in the inner glow of afterhours. There was a sense of belonging in these fractured glances, and in the smooth strides of a man who zipped down 19th street on rollerblades while chatting with his bluetooth’d self Each of these sightings registered a pang of longing that sung through my heart.

(I recalled, as I often do, a memory of a rainstorm at dawn several years ago, my green bedroom syrupy and sunlit and full of friends sprawled out on mattresses and in chairs, long bouts of listening interspersed with sleepy jokes and lazy laughter. Joe had set up a feedback contraption that captured the sounds of the falling rain and catapulted them back into the room. Drenched in sound and in the love of adopted family close at hand, I remember falling asleep with the acute sense that I had come full circle back to my childhood, to the warmth of s’more-infused campfires and sunday night baths with my siblings.)

Then I remembered that sunlit day, which proceeded into an evening of laughter, ranting, and friendly camaraderie with a friend I’d never gotten to know well one-on-one. There was a point where I found myself persuading her to look at San Diego, to come and make a community of smart, down-to-earth compadres. It occurred to me just how necessary such dreams had become, lost in the sea of anomie that is new york city.

This was all only ever temporary, a sacrifice for love. Never inclined toward urban environments, I resolved not to become too attached to this city – just as I’d resolved, 5 years ago, not to fall in love during the year I was abroad in Denmark.

That pact failed back then – of course during the last two months of my stay, with nothing to stand in the way of letting go – I fell in love with a Danish boy destined for the Danish military life, just as I was destined for the American collegiate life. I’ve no regrets. How could I?

And so I’ve no regrets for my renewed mission: to love this porous city for all its flaws and elegant superstructure, to capture this life so rich with culture and madness, and finally to know what it means to escape the zoo of my own accord.

From the mid-19th century California Gold Rush to the turn-of-the-20th century cinematic fame of Hollywood, the furthest-west segment of the United States has inherited the legacy of the New Frontier. Today, the San Francisco Bay Area serves as the nexus of American utopianism, home of Silicon Valley and the dot-com frenzy, haven for hippies new and old.

I seek not to conclude my research of online social networking, but to extend its implications and apply it toward understanding the interconnected mysteries that keep me captivated by anthropology. The literature of cyberspace has quite literally predicted the future now within which we are currently living. The first step, then, is to become familiar with this literature, ranging from science fiction books and films to new ways of crafting contemporary folklore through the use of modern media technologies.

I’ve been chatting with James Curcio, author of Join My Cult! and, more recently, Fallen Nation. They’re also on my summer reading list, and fit quite neatly into the literature I’m looking to submerge myself in (indeed, our chats have been a substantial part of the inspiration behind this post). I’m hoping to contribute to one of his new projects,Mythos Media, which seeks to produce contemporary myths in new ways through the use of new media. Thus, the second step is my own active participation in storycrafting, immersing myself in the mythology of the future-now and constructing parables utilizing new technologies.

From the open source culture of the Internet to the gift culture found at Burning Man and psytrance parties, the mythological legacy of California depicts all the essential dramaturgical elements: a paradisiacal land of angels and devils replete with struggles for power, legitimacy, and authenticity in an age where the world stands poised on the brink of apocalypse, anxiously awaiting salvation in the form of a charismatic prophet, a new world order, scientology, etc;

Or global consciousness.

The third and simultaneous step is a paper I am currently writing for an edited collection on psytrance culture, entitled Weaving the Underground Web: Neotribalism and Psytrance on Tribe.net.

Essentially, I’m building on the segments of my thesis that dealt with Tribe.net and subcultural capital theory, discussing the ways in which members of Tribe.net utilize the site as a facilitator of local scenes as well as a conduit for the spread of a global subculture.

The culture of the New Age (defined by Steven Sutcliffe [2003] as “a diffuse collectivity of questing individuals”) circulates through the intersection of a wide array of beliefs and lifestyles that coalesce with the aid of such liminal spaces as the internet and international psytrance gatherings. Today, this mythology pervades in American popular media, which circulates readily on a global scale. Proper experience of this “global underground” is thus twofold, entailing both online ethnography of Tribe.net as well as adventures around the world- but that will probably have to wait until I find a Ph.D program suitable for this project. That would be step four.

Comments, suggestions, conversation welcome and encouraged.

Mika, a friend from high school, had been going through a “Facebook-identity crisis” over the past couple of days; each time I had logged into Facebook during this time, the “Recently Updated” tab indicated that Mika had changed several elements of his profile. Often, his changes would include a reference to the Facebook medium itself. At one point, his profile was exceedingly honest and somewhat vulnerable, his “About Me” declaring himself to be a “nice, open-minded guy,” inviting others to talk to him and get to know him more. However, this brief display of stark honesty was quickly deleted, to be replaced by a more minimal, utilitarian profile.

Curious, I sent him an IM (instant message) and struck up a conversation. Though he admitted to occasionally “giving Facebook a shot,” in assessing these attempts at honest self-portrayal he put himself in the position of someone else viewing his profile and came to the conclusion that “I would think I’m a loser.” He noted the inadequacy of Facebook profiles for truly getting to know others, particularly those he had recently met but had yet to develop a good friendship with, and expressed his desire to be able to connect “directly to people’s brains.”

His observations, spurred by his experiences with Facebook, can be applied to virtually every medium of human communication- beginning with language itself. As the early 20th-century philosopher-poet T.E. Hulme puts it: “Language is by its very nature a communal thing; that is, it expresses never the exact thing but a compromise—that which is common to you, me, and everybody.” From face-to-face conversations to modern technologies of communication, our experiences of the world are mediated by language. Through language, humans develop mutually understood symbols by which we define ourselves, our worldviews, and reality itself.

The struggle to effectively communicate one’s “true” self is not particular to online social networking; rather, the tension between one’s inner sense of self and outward portrayal of that self had been a subject of concern in Western culture long before the advent of the Internet. From the dawn of recorded language, Plato spoke of the “great stage of human life.” If, as Shakespeare mused, “All the world is a stage, and all the men and women merely players,” then what happens when the curtains close and we go backstage? In The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Erving Goffman (1956) elaborated upon this dramaturgical approach in crafting a sociological theory that has come to be known as “symbolic interactionism.” Once backstage, “the impression fostered by the presentation is knowingly contradicted as a matter of course (112).” From the symbolic interactionist perspective, one performs a certain role on the public stage that is often subverted in the private sphere (“backstage” . This private sphere allows for a more “truthful” performance of self, but is nevertheless still a performance tailored to a specific audience. The question then becomes: may one understand the “true self” when no audience is present? . This private sphere allows for a more “truthful” performance of self, but is nevertheless still a performance tailored to a specific audience. The question then becomes: may one understand the “true self” when no audience is present?

Paul Ricoeur, an eminent scholar in the field of hermeneutics and phenomenology, challenges the notion that the self is transparent to itself. Rather, he theorizes that the hermeneutic self is revealed to that self through the ‘other’- immediately and directly through two interlocuters. Furthermore, this face-to-face, intersubjective encounter is a relation that is “invariably intertwined with various long intersubjective relations, mediated by various social institutions, groups, nations and cultural traditions (Kearney 2004: 4).” One continually attempts to define the self as an individual with a unique “personality,” however this process is itself co-constructed through one’s everyday interactions with others as well as the subjective appropriation of various cultural markers of identity. From this perspective, online social networks mirror the process by which individuals construct their identities by extending interpersonal communication and providing fields in which they may articulate their cultural tastes and group affiliations.

Despite the evidence that all experiences are mediated and that the “self” is co-constructed, I have time and again encountered the pervasive belief that experiences with online social networking diminish the quality of interpersonal communication and fail to accurately portray one’s identity. This perceived disconnect may be attributed to a number of factors.

Firstly, computer-mediated communication reduces the kind of social cues we frequently rely on in face-to-face communication (such as gesture and intonation), thereby increasing the likelihood for miscommunication.

Secondly, effective computer-mediated communication demands not only literacy and the ability to effectively communicate through written text, but also a certain level of “fluency” with the specific language of the online environment in which one is participating.

Thirdly, popular online social networks pose the threat of enmeshing myriad social contexts, effectively challenging the distinctions between public and private. In these cases, the protective boundaries between the various roles we perform “onstage” and those we perform “backstage” become dangerously blurred.

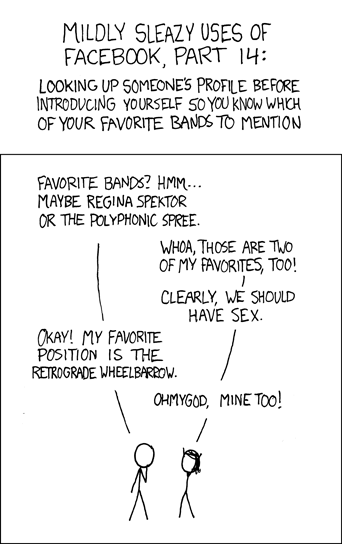

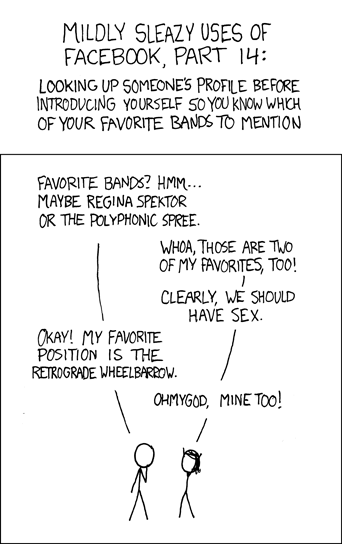

Finally, because these audiences are often invisible, we may come to know more about another through their online personas than through “natural” face-to-face interactions, and vice versa. In such cases, the “self” is projected rather than co-constructed, substantially altering the process through which we come to know another. The awkwardness of this new social phenomenon is humorously portrayed in a comic I recently came across:

In 1991, Hakim Bey published a work entitled TAZ: Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, and Poetic Terrorism. The TAZ is essentially that liminal space that exists on the edges of things, the moments that allow for true creativity that occur outside of the hierarchical structures of society and information. True freedom and empowerment is found only in these moments. Though we often conceive of the Internet as a liminal space in which structural hierarchies are dissembled, Bey differentiates between “the Net” as the hierarchical structures of information flow, and the “counter-Net”, which are those clandestine and rebellious practices that subvert this hierarchy (think music downloading…). The “Web”, then, enables open and horizontal patterns of information flow. Together, the three comprise the system that make up the Internet. Some great questions are posed- I’ve excerpted my favorite bit below:

“Also I am not impressed by the sort of information and services proffered by contemporary “radical” networks. Somewhere–one is told–there exists an “information economy.” Maybe so; but the info being traded over the “alternative” BBSs seems to consist entirely of chitchat and techie-talk. Is this an economy? or merely a pastime for enthusiasts? OK, PCs have created yet another “print revolution”–OK, marginal webworks are evolving–OK, I can now carry on six phone conversations at once. But what difference has this made in my ordinary life?

Frankly, I already had plenty of data to enrich my perceptions, what with books, movies, TV, theater, telephones, the U.S. Postal Service, altered states of consciousness, and so on. Do I really need a PC in order to obtain yet more such data? You offer me secret information? Well…perhaps I’m tempted–but still I demand marvelous secrets, not just unlisted telephone numbers or the trivia of cops and politicians. Most of all I want computers to provide me with information linked to real goods–“the good things in life,” as the IWW Preamble puts it. And here, since I’m accusing the hackers and BBSers of irritating intellectual vagueness, I must myself descend from the baroque clouds of Theory & Critique and explain what I mean by “real goods.”

Let’s say that for both political and personal reasons I desire good food, better than I can obtain from Capitalism– unpolluted food still blessed with strong and natural flavors. To complicate the game imagine that the food I crave is illegal–raw milk perhaps, or the exquisite Cuban fruit mamey, which cannot be imported fresh into the U.S. because its seed is hallucinogenic (or so I’m told). I am not a farmer. Let’s pretend I’m an importer of rare perfumes and aphrodisiacs, and sharpen the play by assuming most of my stock is also illegal. Or maybe I only want to trade word processing services for organic turnips, but refuse to report the transaction to the IRS (as required by law, believe it or not). Or maybe I want to meet other humans for consensual but illegal acts of mutual pleasure (this has actually been tried, but all the hard-sex BBSs have been busted–and what use is an underground with lousy security?). In short, assume that I’m fed up with mere information, the ghost in the machine. According to you, computers should already be quite capable of facilitating my desires for food, drugs, sex, tax evasion. So what’s the matter? Why isn’t it happening?

The TAZ has occurred, is occurring, and will occur with or without the computer. But for the TAZ to reach its full potential it must become less a matter of spontaneous combustion and more a matter of “islands in the Net.” The Net, or rather the counter-Net, assumes the promise of an integral aspect of the TAZ, an addition that will multiply its potential, a “quantum jump” (odd how this expression has come to mean a big leap) in complexity and significance. The TAZ must now exist within a world of pure space, the world of the senses. Liminal, even evanescent, the TAZ must combine information and desire in order to fulfill its adventure (its “happening” , in order to fill itself to the borders of its destiny, to saturate itself with its own becoming. , in order to fill itself to the borders of its destiny, to saturate itself with its own becoming.

Perhaps the Neo-Paleolithic School are correct when they assert that all forms of alienation and mediation must be destroyed or abandoned before our goals can be realized–or perhaps true anarchy will be realized only in Outer Space, as some futuro-libertarians assert. But the TAZ does not concern itself very much with “was” or “will be.” The TAZ is interested in results, successful raids on consensus reality, breakthroughs into more intense and more abundant life. If the computer cannot be used in this project, then the computer will have to be overcome. My intuition however suggests that the counter-Net is already coming into being, perhaps already exists–but I cannot prove it. I’ve based the theory of the TAZ in large part on this intuition. Of course the Web also involves non-computerized networks of exchange such as samizdat, the black market, etc.–but the full potential of non-hierarchic information networking logically leads to the computer as the tool par excellence. Now I’m waiting for the hackers to prove I’m right, that my intuition is valid. Where are my turnips?”

My virtual wandering through the thousands of bulletin boards that make up Tribe.net exposed me to two terms I’d never heard of before, but instantly caught my attention: technoshamanism and neotribalism. Both terms evoke a somewhat romantic notion of merging modern technologies with our ancient tribal past. For instance, certain kinds of electronic music are claimed to have the capacity to induce trance-like states that are shared by a group of people through ecstatic dance, evoking images of shamanic tribal rituals in various parts of the world (such as South America, India, and Africa). Synthetic drugs such as LSD (“acid”) and MDMA (“ecstasy”) are frequently ingested as well, to aid in inducing trance-like states, altering visual and auditory perceptions, and enhancing feelings of connectedness to others and the “divine within”. In the words of one Tribe.net member:

“To me, [technoshamanism] is getting in touch with the past and uniting it with the present. Our species has danced the night away to a rhythm and beat for as long as we have had consciousness to do so. Whether it be an animal hide-based drum, or a drum machine the sound is the same. If music in general was compared to say, the English language, its beat and rhythm would be the vowel sounds that make up every word in existence. Understood by all who hear it regardless of ethnicity or creed.”

Various parallels with these ideas/beliefs can be found with religious movements: prophetic figures have emerged throughout the past half-century (such as Timothy Leary, Terence McKenna, Alex Grey and Daniel Pinchbeck), some of whom espouse the belief (traces of which can be found throughout the site) that the world will either come to an end in the year 2012, or become embroiled in a global spiritual transformation (this theory is rooted in the Mayan Calendar, but I won’t get too gritty with the details. It’s all widely disputed by Mayanist scholars). “The tribes and the primitive people will survive,” predicts a 50-year old Californian man, “know how to get all that you need from the earth. Nothing else can be expected to survive.” Like the Back-to-the-Land movement of the 1960’s, neotribalists seek a return to humanity’s “ancestral roots” through developing local, self-sustaining communities, with an emphasis on creating a global network of interconnected tribes. The Internet is, quite naturally, one of those modern technologies that is utilized by technoshamans as a means of tapping into the collective neural network.

Underlying the ideology of neotribalism is the concept of a universal consciousness that has been forgotten in the wake of civilization, and that must be rediscovered if humanity is to survive. A technoshaman, then, is a guide, one who integrates modern technology into primordial practices in order to induce transcendent experiences. Now, such a description evokes remnants of that anthropological black mark- the noble savage. From my vantage point, it feels a bit shameful- white hippies “going tribal,” attempting to appropriate cultural practices that have developed over centuries.

[Edit: Thanks for the feedback. My feelings about its shamefulness extend from my own personal experiences with such practices, and wondering, at times, if we are being duped into the sense of communitas- often brought about only through the aid of drugs. I’ve thrown many such parties, where I provided no drugs, in an attempt to see if *it* could be spontaneously generated without such additions… I failed, but that doesn’t mean I’ll stop trying…

I agree, we are enculturated to look down on such practices. And that’s fucked up.]

Your feedback is strongly encouraged… tap into my neural network, damnit!

I ran across an interesting thread on Tribe.net yesterday entitled “What is Technoshamanism?” You can read it here, but in a nutshell, the respondees described technoshamanism as a means of uniting the past and the present, or the spiritual and the technological. From dancing around a bonfire to the beat of the drums, to dancing all night long to electronic trance music, the end goal is a spiritual connection to the universe that dates back to the beginning of humankind’s time on this planet.

I have to simply marvel, at times, how meticulously the system of Facebook is run. Nothing is deleted, all is stored. Upon deleting my Facebook account, I learned that the moment I logged in again, my entire account- the photos, the messages, the wall posts- would be rekindled from my momentary lapse of Facebook identity, as if I had taken a vacation… which, admittedly, I had.

The new frontier for individualism, the virtual frontier, is at this point still an open one. However, as this sphere becomes increasingly dominated by large corporate networks, understanding the illusory nature of agency is critical. John Barlow’s Declaration for the Independence of Cyberspace has never been more poignant.

Asked to attempt a summation of the online social networking community known as tribe.net, I have taken to replying with the single phrase, “technoshamanism”. It seems the word has not yet been taken up by many, so I’ll attempt a definition here.

(For a little background information, you’d be keen to check out a term project I worked on for my Anthropology of Dance class, entitled “The Trance Dance Experience“)

A technoshaman is one who integrates modern technology into primordial practices in order to induce transcendent experiences. Now, such a description evokes remnants of that anthropological black mark- the noble savage- and thus I proceed with caution, unwilling to romanticize:

Technoshamanism seeks to rediscover the roots of human experience while utilizing modern tools. Such tools can range from repetitive electronic music, to synthetic drugs, to new technologies such as biofeedback. The states thus induced might range from supersensory to meditative. Modern “rave” culture (and I use this term with caution as well, for the rave scene has become inundated by the mainstream, thus necessitating an emergent subculture(s)) incorporates just such tools to achieve just such states, and where site and ideology merge, we have our subculture.

Regardless of terminology, the essence of such subcultures is the pursuit of the collective unconscious, consciously realized and enacted. When I say “neotribal,” I refer to the tribal experience as it is recreated in the modern day. Safe spaces are created through collective artistic action; drugs consumed that serve to enhance feelings of empathy, community, clairvoyance, and/or transcendence; music played that serves to enhance said feelings and provide the collective pulse. This occurs with varying degrees of success, depending on whether individuals collaborate effectively to achieve the same goals.

The Internet is, quite naturally, one of those modern technologies that is utilized by technoshamans as a means of tapping into the collective neural network. As it exists apart (or, at the very least, disjointed) from time and space, the shape and texture of the Internet resembles that of technoshamanism itself. That’s all I’ve got for now.

I was notified via Tribe.net today of a new online startup by Daniel Pinchbeck (Technoshaman, Wesleyan dropout, and author of Breaking Open the Head and 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl), Reality Sandwich. The site is to begin as an online magazine dedicated to the “re-imagining” of an intentional, international community of new-age shamans and neo-hippies. It is planned to evolve into an extensive, global social networking site. Among the first articles can be found discussions of the “ethnosphere”, an interview with Abbie Hoffman, 21st century shamans, a “recipe for happiness” and an article about the practical application of digital utopian ideals in Web 2.0 communities.

My primary focus in blog will be the ongoing struggle to create an Internet that serves the public interest, one that incorporates the highest ideals that the evolution of web 2.0 points toward. I will watch the industry and I will watch the tech watchers and give you my honest perspective. I will tell you about companies that are doing good work and trying to improve things, and alert you to those that are being sneaky. In the same way as buying green produce supports and helps people make deeper changes in industry practices, we can vote with our on-line attention and dollars, giving our business to those online companies who put you in the middle of the picture.

Pinchbeck is a controversial figure in New Age discourse, and has been described by many as a modern-day Timothy Leary, though Terence McKenna is a more appropriate comparison. His ambitious goals to evolve the global consciousness through the appropriation of technology and communication practices is reminiscent of Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog (see From Counterculture to Cyberculture, part 1 and part 2).

Implications for Research

Is this a new stage in the rise of digital utopianism? Are we witnessing the rise of technoshamanism? How does this New Age subculture find strength in global, online communities (such as Tribe)?

Based on fieldwork amongst a community of online gaming fans, Knorr argues that the field of anthropology is well-suited for the study of online communities as sites of sociocultural appropriation. The habitat of an online community is located within the Internet infrastructure, a dynamic space that utilizes multiple forms of mediated technology. Rather than limiting communication to the common shared interest, members of the group exchange gossip, create hierarchies, and establish new spaces for group interaction when older forms are obliterated. The community in question is described as a “nomadic tribe” that retains interpersonal structure regardless of geographic or even Internet space. The members of this community can best be described, not as consumers of technology, but as active creators of their online habitat. In this sense Internet communication technologies are reconstructed through a process of appropriation. So too are social networking communities appropriated as they are reworked to suit individual groups, as is the case in online activism and the geographical dispersion of subcultures.

|

|

. This private sphere allows for a more “truthful” performance of self, but is nevertheless still a performance tailored to a specific audience. The question then becomes: may one understand the “true self” when no audience is present?

. This private sphere allows for a more “truthful” performance of self, but is nevertheless still a performance tailored to a specific audience. The question then becomes: may one understand the “true self” when no audience is present?

, in order to fill itself to the borders of its destiny, to saturate itself with its own becoming.

, in order to fill itself to the borders of its destiny, to saturate itself with its own becoming.