|

|

On December 2nd, as soon as the purchase of the Omni Commons was finalized (!!!), I packed up my car and took off for the Standing Rock Sioux reservation (located about 1600 miles northwest) with a comrade to join the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline. Over the previous two months, I’d been looped into the Tech/Comms team on the ground via another comrade, Lisha Sterling from Geeks Without Bounds, and had been advising on building out a local area or mesh network to help with connectivity and communications issues on the ground.

We arrived during one of the more tumultuous times at camp, as the population had spiked to over 12,000 people – many of them hugely unprepared and underequipped for the arctic conditions of North Dakota in December. It was an intense experience personally for many in our community – halfway through our trek across the country, friends and relatives reached out with horrific news: over 30 people, most of them young artists and activists embedded in the social fabric of our lives in Oakland, had perished in the tragic Ghostship warehouse fire that weekend.

So we arrived, shaken and heartbroken and more than a little sick of each other’s company to boot. The final miles of our journey into camp were a slow crawl behind hundreds upon others who’d come in solidarity – but just as many hundreds of vehicles headed out of camp. Apparently, the judge had denied the easement that would enable DAPL to continue constructing the pipeline that month, and approximately half the camp concluded this was a victory. We arrived to a bewildering scene: reuniting with brokenhearted friends from Oakland, firework celebrations and partying over a perceived victory we knew was short-sighted, and the first dangerously-low temperature dip of the season: -10°F (-23°C). Over 30 people that night were reported by Medical as hypothermic.

I was so incredibly grateful when Lisha greeted me with news that the Tech Tent had just been outfitted with a stovepipe, and that bunkbed cots were on the way. After spending my first day getting oriented and making the Tech Tent habitable, I recorded my first livestream:

That week, given the timing, was largely spent orienting myself, trying to understand what the fuck was going on with continual actual threats as well as false alarms triggered by the State, constantly-shifting internal community power dynamics, and multiple small emergencies daily (such as bringing a generator to a camp whose horse trough had frozen over). Lisha was horrifically sick with a bronchial infection (as were many at camp, thanks to a killer combo of cold, smoke, and stress), and the majority of the tech crew had just left. I found myself faced with one of the more challenging set of circumstances I’ve experienced in my life: rapidly adapting to extreme and unfamiliar conditions whilst balancing the need to listen and deeply understand a sacred space and struggle with the call for active leadership on the technical and communications front.

It was bitterly ironic to be burning wood and propane when we had an abundance of resources for building a sustainable energy grid – then again, these were critical environmental and psychological conditions unlike most anyone has ever known. At times, it was hard to think about anything other than how to warm one’s fingertips. Nevertheless, I was staying in a comparably toasty tent full of solar panels, wind turbines, and radio equipment – hella privileged, I had to admit, as I hauled hay bales generously donated from the back of the Wellbeing Tent to provide a layer of insulation around the Tech Tent. We had a stockpile of much-needed gear, but not much in the way of a crew capable of deploying it. So, I set out to build a crew – focusing first and foremost on power.

As is often the case in communities bound together by a unifying cause in the face of a powerful enemy, it didn’t take long to find the others. By the end of the week, we had a skeleton crew of smart, capable techies making the Tech Tent one of their home bases, had inventoried and tested our equipment, and had begun to deploy power crews to most-needed locations whilst collating a map and a plan for the rest of the camp.

A week or so into my arrival, the main public hotspot (a Ubiquiti NanoStation M5 running on stock firmware with a point-to-point connection to the Wellbeing Tent at the base of Media Hill) disappeared from its semi-prominent location at the dome in what was clearly an act of sabotage:

Luckily, I’d brought a few routers (MyNet N600s) already pre-flashed with the sudomesh firmware. I set one up in the Wellbeing Tent with a direct ethernet cable connection to the directional antenna receiving internets from the hill, and another one inside the dome. With a range of ~100 meters, the two nodes were able to see each other and mesh easily. Both tents now hosted open peoplesopen.net hotspots in addition to the private ssid at the Wellbeing Tent, the password for which was distributed to indigenous leadership as well as the tech and media crews.

A few days later, I met a comrade from Sacred Stone who shared some footage of sabotage they’d uncovered at the other end of camp – a perfect-condition snowplow destroyed by way of removing a critical part; additionally, several power lines and insulated water pipes destroyed. But the sabotage was merely the tip of the iceberg of psychological warfare waged against the Water Protectors – from the fire hoses in sub-zero temperatures to the nonstop, creepy trolling of all of our walkie-talkie channels, there was no possibility of escape from it.

I wasn’t at Standing Rock long – a mere two weeks, buffeted by the Omni building purchase into December and a long-planned trip to Africa with my partner’s family at the end of the month – but I learned more in those two weeks than I can even begin to articulate in this post. The importance of trust (AND paranoia) in liminal spaces of contention, maintaining internal peace in the face of at-times violent chaos, organizing with humans who’ve reached their physical and psychological limits, carrying on and doing what needs to be done when all hope seems lost, and ultimately, finding grounding and humility in serving the indigenous leadership protecting and honoring Maka Ina – Earth Mother.

My final livestream, sounding much hoarser and wearier:

This summer marked the 8th annual Battle of the Mesh in beautiful Maribor, Slovenia at the foot of the Swiss alps. Each year, folks from around the world who work on open source mesh networking protocols (schemes for routing packets across a network) and community wireless networks converge to deploy a testbed mesh network, running different protocols on top of it and analyzing which of them perform the best.

Mount Pohorje in Maribor, Slovenia, site of BattleMesh v8! This year, the conference agenda also included a wider variety of topics, from decentralized and secure file systems and applications to political discussions about the future of open hardware and firmware in the face of imminent federal regulatory lockdown measures.

The first day was largely spent socializing and setting up the topology of the network:

Topology of the testbed network built at BattleMesh v8 Five actively maintained and deployed routing protocols were tested over the course of the week:

* Babel, a distance-vector routing protocol for IPv6 and IPv4 largely developed by Juliusz Chroboczek in France;

* Batman-adv, an implementation of BATMAN [Better Approach to Mobile Ad-hoc Networking], spearheaded by the Germany-based Freifunk community;

* BMX7, an experimental protocol designed to bridge Layer 2 and Layer 3 routing;

* OLSRd1, short for ‘Optimized Link State Routing’ and widely utilized in many of community networks due to its stability, scalability and active development community,

* OLSRd2, a new iteration of OLSR designed to be more modular and flexible, published by the IETF in 2014.

Day 2 started out rather chaotically, as a dozen wireless hackers attempted to fix the internet they’d borked. The afternoon’s talks featured an excellent presentation by Julius, the lead developer of Babel, entitled ‘babel does not care.’ You can watch the talk (with accompanying slides) here. Julius’ talk was followed by a presentation of GNUnet, a free-as-in-freedom alternative and privacy-conscious network for peer-to-peer filesharing, VOIP communication, and peer discovery that works over a variety of transport mechanisms. Watch the full talk with slides here. Next, Elektra of Freifunk gave a presentation on the current state of TV whitespace spectrum and the potential future applications of UHF. I highly recommend watching the talk, as Elektra concludes with a stirring call-to-action for the community to engage with the political struggle over spectrum allocation, one unfairly slanted toward powerful telecommunications companies over free and open community network usages.

Day 3 kicked off with a presentation by Mathieu Boutier on source-specific routing in Babel [Video]. Next came a presentation on cjdns, a distributed and end-to-end encrypted p2p IPv6 meshnet project better known as Hyperboria. They have just begun collaborating with a fascinating project called IPFS, the Interplanetary File System, which combines ideas from Git, Bittorrent, and the web to enable such applications as peer-to-peer filesharing through creating a distributed content cache accessed through a hashed URL. Check out their talk, which appropriately followed the cjdns presentation. Folks from Battlemesh are using IPFS to store media content uploaded by conference participants!

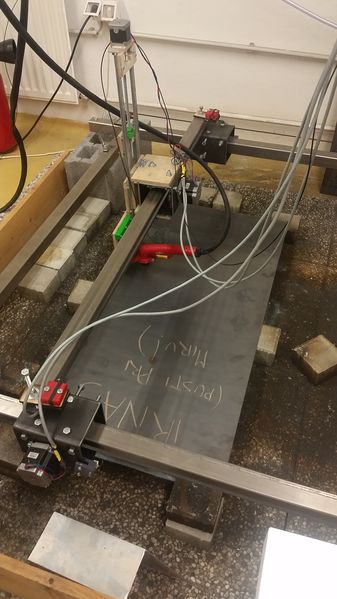

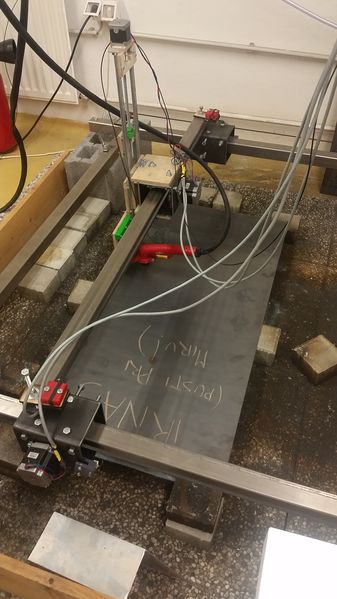

An easy-to-assemble, open hardware plasma cutter from Irnas. We celebrated the mid-point of the conference by spending the afternoon and evening in Maribor, first with a tour of KreatorLab. KreatorLab is home to a bevy of inspiring open hardware projects, including a plasma cutter, a 3D printer, and Koruza, Musti’s brainchild enabling gigabit wireless optical links.

After our visit to KreatorLab, we headed over to the GT22, a self-described “transdisciplinary laboratory in real space with transnational guerilla art school institutes” hosting space for theater rehearsals, a radical library, a photography museum, an indoor skating ramp and a party space populated by a VJ projection screen and a DJ booth. While the DJ played dance music, our true-to-form hackers proceeded to gather outside and along the walls not dancing 🙂

Thursday, Day 4 of the conference, began with a presentation of Cake (Comprehensive Queue Management Made Easy), a project that works to make wifi faster by reducing network latency. The following presentation by Dave Taht provided an excellent overview of the current insecurities in Internet of Things devices outlined across 11 layers of the network stack, culminating in a rousing call-to-action for hackers to build more and better open hardware. I highly recommend watching this talk!

Dave’s talk was a fitting antecedent to the subsequent presentation and discussion of the FCC’s recent proposal to lock down wireless routers by requiring vendors to “ensure that only properly authenticated software is loaded and operating the device.” This has huge implications for community networks in the US, with similar rules being discussed for the EU and Canada. After a heavily animated discussion, folks continued to discuss the issue over lunch, with many inspired by Dave’s talk to create our own hacker-friendly hardware down to the chipset level. We created a mailing list to collaboratively compose letters to the FCC, the comment period for which has recently been extended to October 9th and is open to everyone.

Unfortunately, I missed the entirety of Thursday afternoon’s talks as I literally sat in the same spot at our lunch table conversing with new friends into the evening.

Friday kicked off with a presentation from Demos to consolidate and test various decentralized applications with the aim of supporting a more decentralized web. She was followed by Nemesis presenting, NetJSON and Nodeshot, projects working to build node databases for network monitoring and administration. After lunch, Paige gave an impressive presentation on MaidSafe, a secure and decentralized storage and communications platform.

On the last day, a few of us set up a video camera and did short interviews with representatives from as many community wireless networks as we could gather. The focus of the interviews was to explore the various motivations and unique challenges faced by a diversity of community networks, with the aim to inspire and guide the development of many more to come. Watch this blog for updates once the videos have been edited and posted to the web!

So… which protocol won?

Given the complexity and variety of tests and analytics, the ‘winner’ is difficult to determine. Check out the beautiful (and nearly complete!) documentation, including detailed graphs and links to git repos of the software used to test the network here.

Please drop me a line at jenny [at] sudomesh [dot] org if you’d like to help plan for the very first ‘BattleMesh West’ at the Omni Commons next year!

Last Saturday marked the final day of the Bay Area Public School’s weeklong Summer School, the theme of which was Information. We started the day with a Cryptoparty – hands-on workshops to assist folks in generating key signatures, using encrypted and off-the-record chat, and other tools such as Tor and Redphone – this went really well, with lots of folks leaving having learned new skills or solved a particular problem, and all culminated in a delightfully geeky key-signing party.

There were a bunch of great talks:

* My housemate, Craig Rouskey, gave an amazing presentations on his citizen science project to eradicate gonorrhea using phage therapy.

* Marc Juul and I presented on our project to build a mesh network in Oakland!

* The lovable Danny O’Brien spoke about the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s work in fighting for digital civil liberties and why privacy and digital security are important.

The day culminated in a panel with Moxie Marlinspike (of Whisper Systems), Danny, Bill from the EFF, Marc and myself, with the attendees participating in a Q&A.

THEN WE PARTIED. IT WAS AWESOME.

Notes and link to the livestream (mad props to JC!) are here: https://sudoroom.org/wiki/Cryptoparty/2013/August

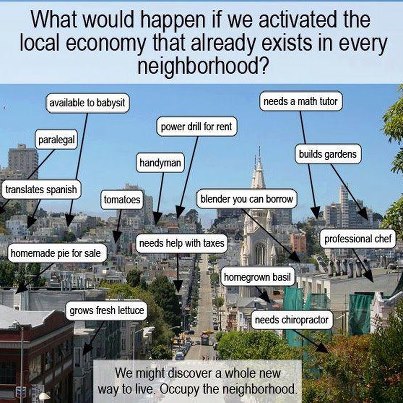

Hyperlocalism seeks to bridge the physical/digital divide by focusing on the use of information to create technology tools and media oriented around a well-defined area and inspired by the needs of local residents. Maps and mesh networks are tools that can be particularly leveraged to enable hyperlocal connectivity and information flow; I’ll briefly unpack the latter (mesh) and then demonstrate the possibilities for hyperlocal mapping.

510pen as conceptualized by Mark Burdett is based on the principles of the Open Wireless Movement: that by sharing our wifi with our neighbors, we contribute to increasing access to the internet while simultaneously creating more positive relationships with our local communities. This premise is clearly the most obvious benefit of mesh networking and is enthusiastically supported by the folks I’ve been talking with in Oakland, who see the lack of widespread internet access in their neighborhoods as a very present and real issue.

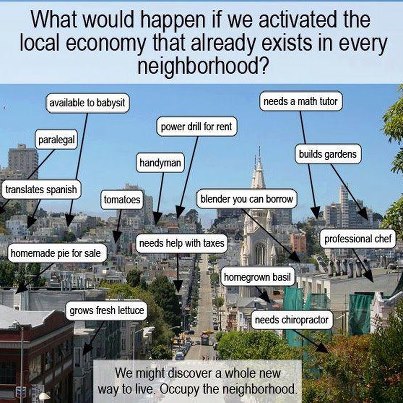

Then there is the application layer – which is the level at which TidePools is working to create software for hyperlocal neighborhood mapping. Beyond internet access, a resilient communications network endeavors to create point-to-point networks that mesh the barriers between physical and virtual space. What kinds of data and landmarks define the available resources and value of a physical community?

It might look something like this:

…in which the skills and resources of your neighbors are made visible and available to others on the local network.

Or perhaps like this, visualizing the history of a neighborhood through a timeline-based photographic montage:

Alternatively, we could use hyperlocal mapping to depict a more realistic sense of the cultural characteristics of various neighborhoods, rather than the oft-arbitrary borders drawn by state governments:

As I continue interviewing and chatting with folks about things they’d love to see on local maps, a few themes have emerged:

Environmental activists seeking to visualize pollution data, park locations, local wildlife, etc;

Unemployed and homeless folks seeking to map out resources such as public computers, food kitchens, excellent dumpsters for food foraging, and crisis centers for various demographics.

Long-term residents wishing to map out and connect local businesses and organizations in their neighborhoods.

Community organizers interested in mapping their community to strengthen awareness of existing resources and publicly accessible spaces.

Hackers and techies interested in creating decentralized networks and alternative telecommunications (eg; mesh networks, low-bandwidth software radios, etc;) – which necessarily requires mapping line-of-sight on rooftops and potential barriers to connectivity (such as raised highways)

Open government folks mapping open civic data such as crime, foreclosed / blighted properties, city legislative initiatives, and historical information.

Here are some projects I’ve been working on with some other hard-working, socially-conscious people that are tackling these needs:

Tidepools – Hyperlocal neighborhood mapping software.

510pen (Five One Open) – Creating an East Bay mesh network.

Open Oakland – Volunteers mapping out open civic data in Oakland.

OpenOakland Digital Divide – Mapping out existing Oakland efforts addressing the issue of access to technology.

Oakland Wiki – A site all about Oakland, with over 2,000 articles written by community members.

Mycelia – A decentralized database I’m working on with my partner for mapping tools/inventory, skills, and projects between and among hackerspaces, intentional communities, and other self-organizing spaces.

I welcome and encourage further suggestions and use cases in the comments below!

Last month, I spent several days staying with some friends in Brooklyn, New York who’ve been working full-time with Occupy Sandy‘s relief/rebuild efforts. While the devastation wrought by Hurricane Sandy has been heartbreaking and the lack of federal response infuriating, the kind of connectivity and mutual aid that has emerged in the resulting months is nothing short of inspirational. And profoundly educational.

Here are the meeting minutes from the network-wide Occupy Sandy meeting I attended right before the December solstice. It was the most well-facilitated meeting I’ve ever participated in, with the focus primarily being upon sharing updates from representatives of the disparate groups organizing Sandy relief efforts in the Far Rockaways, Red Hook, Coney Island, Staten Island, Long Island, and beyond. As Christmas was approaching, the core issue revolved around the many thousands still without heat or electricity. In the Far Rockaways, over 20,000 residents were still without power as freezing temperatures approached. FEMA, overwhelmed and underprepared, had all but handed over its limited resources to the Occupy Sandy camps that had popped up within days of the superstorm. Only this week – more than 75 days after the storm – did Congress approve a bill to send long-overdue federal aid to Sandy victims.

Occupy Sandy, the central hub of which was the amazing Church of St. Luke and St. Matthew (pictured above) in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, sprung to work less than 48 hours after the storm. Tens of thousands of volunteers have since coordinated donations, trained new volunteers, cooked meals for masses of people, scraped mold off of buildings and homes, and assisted residents in completing the paperwork needed for securing governmental aid and navigating insurance claims. There is still a good deal of work to be done to rebuild the neighborhoods destroyed by Sandy, instilling in me a resurgence of passion to develop human and communications infrastructure in preparation for the kinds of crises that can arise when the infrastructure we typically depend upon falls apart.

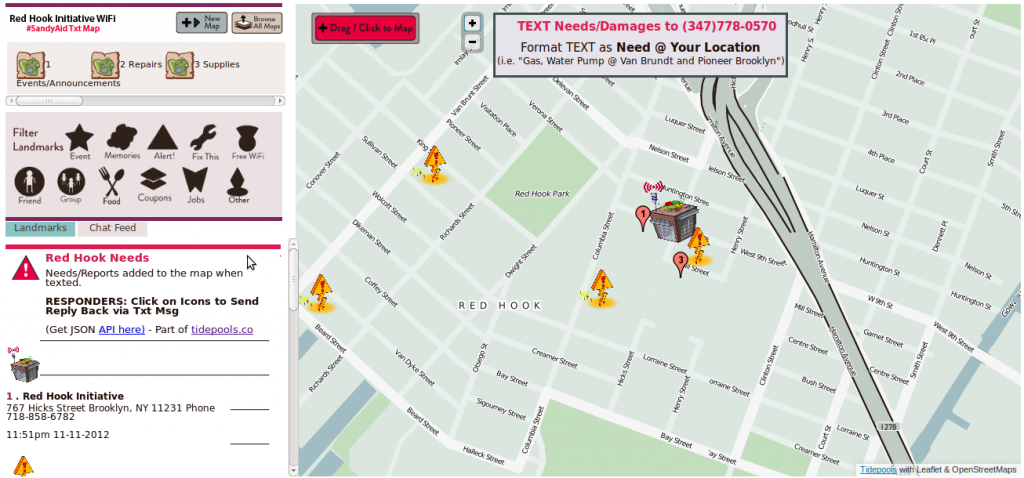

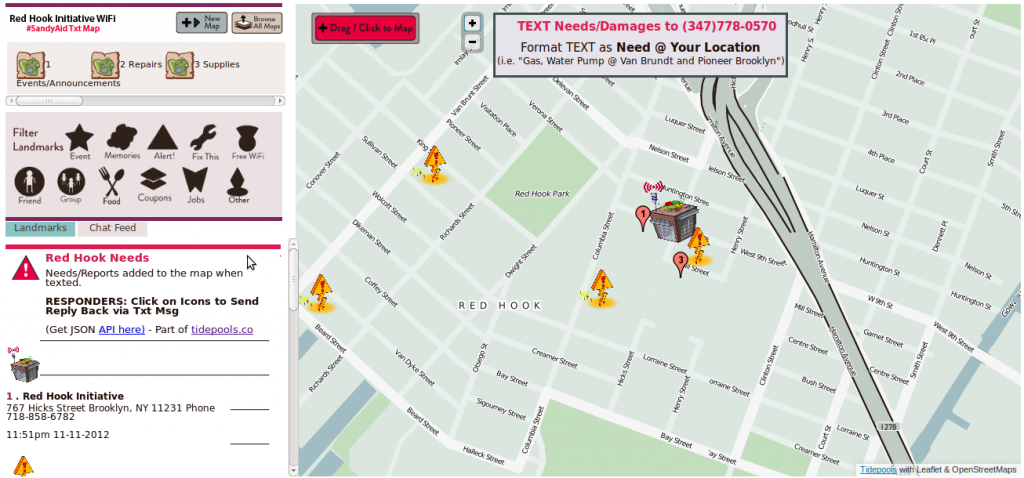

My experiences in New York were concomitant with the exciting news that I’d been accepted for an internship with the Open Technology Institute sponsored by GNOME’s FOSS (Free and Open Source Software) Outreach Program for Women. Specifically, I’ve been tasked with the work of designing use cases for community wireless mesh network applications such as TidePools, a neighborhood mobile mapping platform. TidePools was designed around the particular needs of residents in the Red Hook district of Brooklyn: reporting civic issues such as broken street signs; adding nicknames for the areas around the neighborhood; sharing information about local events; and creating an alert system for the often-spotty public transportation schedules. The potential uses of the platform are too numerous to mention and very much contingent on local context.

Post-Sandy, a TidePools node (pictures above) was deployed for mapping out local needs, sent by residents and volunteers via SMS text messaging for use by first responders seeking up-to-date information on where supplies such as food, water, gas and generators were needed.

You can learn more about my ongoing work for the Open Technology Institute by stopping by the TidePools wiki, where I’m collating ideas, use cases and research surrounding community mesh networking and mapping applications. I’ll also be blogging regularly about mesh applications here, focusing on stories that demonstrate how we can use this technology to facilitate coordination and communication in our local communities. For the latest updates on the Occupy Sandy relief efforts, please visit the online hub at InterOccupy.net.

I’m excited to announce that “Human No More: Digital Subjectivities, Unhuman Subjects, and the End of Anthropology” is finally out and available to order! Human No More began as a delightfully weird, interdisciplinary array of posthumanist scholars in an invited session at the American Anthropological Association Annual Meeting in 2009. Co-edited by Neil Whitehead and Mike Wesch, the book’s topics range from the hive-mind of Anonymous, a wired indigenous tribe in Guyana, the disembodied simulacra of human-bot interaction, and the “humanity” of marginal groups in the context of state-sponsored dehumanization. My own chapter explores how the dead “live on online” through continued presence and interaction via online social networking sites. I’m excited to announce that “Human No More: Digital Subjectivities, Unhuman Subjects, and the End of Anthropology” is finally out and available to order! Human No More began as a delightfully weird, interdisciplinary array of posthumanist scholars in an invited session at the American Anthropological Association Annual Meeting in 2009. Co-edited by Neil Whitehead and Mike Wesch, the book’s topics range from the hive-mind of Anonymous, a wired indigenous tribe in Guyana, the disembodied simulacra of human-bot interaction, and the “humanity” of marginal groups in the context of state-sponsored dehumanization. My own chapter explores how the dead “live on online” through continued presence and interaction via online social networking sites.

This book is dedicated to Neil Whitehead, co-editor and rebel anthropologist, inspiration to us all, who passed away earlier this year. Check out his brilliant, evocative work here.

Turning an anthropological eye toward cyberspace, Human No More explores how conditions of the on-line world shape identity, place, culture, and death within virtual communities. On-line worlds have recently thrown into question the traditional anthropological conception of place-based ethnography. They break definitions, blur distinctions, and force us to rethink the notion of the “subject”. Human No More asks how digital cultures can be integrated and how the ethnography of both the “unhuman” and the “digital” could lead to possible reconfiguring the notion of the “human”. This provocative and ground-breaking work challenges fundamental assumptions about the entire field of anthropology. Cross-disciplinary research from well-respected contributors makes this volume vital to the understanding of contemporary human interaction. It will be of interest not only to anthropologists but also to students and scholars of media, communication, popular culture, identity, and technology.

|

|

I’m excited to announce that

I’m excited to announce that