|

|

Yesterday, I was ‘defriended’ on Facebook by someone who was once a close friend. This isn’t the first time it’s happened – another ex-friend eliminated me from his virtual network last year, but I was but one small proportion of a mass ‘friend-slaying’ – and I’ve most certainly been defriended by a handful of weak ties and acquaintances – but its the first time I’ve really had a previously close connection visually severed as a result of instigating a virtual confrontation. My angry (and rather public) comment was certainly not unwarranted, as this person has long avoided apologizing for deliberately abandoning me when I most needed friendship, but perhaps a little overdue – the only time I had really confronted her about it was nearly nine months ago, after all.

When I realized that she had not just simply deleted my comment, but defriended me in the process, it felt like a punch to the gut that left me in breathless pain for several hours. Now that the smarting pain has subsided, I’ve started thinking that perhaps defriending is actually quite a practical method, and not necessarily just a passive-aggressive move. It’s amazing how much mental space can get taken up obsessing over past injustices, especially once regular face-to-face contact is lost. Certainly this trend becomes particularly prominent post-college. Facebook and related social media can trigger old pathways we’d normally avoid following, delivering a constant stream of “news” and information about those we’d rather be forgetting.

I love the idea of shaking off old grudges and people who evoke negative energy by simply defriending them, but it conflicts with my belief in forgiveness and my sincere desire not to hurt anyone the way my old friend hurt me yesterday. I’d quit the damn book of faces, but I’m pretty deeply invested in it at this point – it’s how I keep in touch with a huge number of friends, stay informed about upcoming parties and events, share my own stories and things I come across on the ‘net that I know a particular person would enjoy, track down a phone number or address when I need it – and, oh yeah, it’s also a major source of my research.

At the very least, I now understand why the ‘friend-slayer’ I mentioned above did what he did. It must be so very refreshing not to be continually reminded of people who make you feel like shit. And now that I’ve written this post, I’ve come to a sense of closure on the matter, myself, and can look forward to totally getting past someone who never deserved as much mental space as I allotted her.

Maybe I’ll turn giving up social media into a little social experiment. I could probably write a book about that experience!

Or maybe I should just choose my friends more wisely…

This post has been much inspired by fellow Facebook researcher and friend, Jeff Ginger, who wrote an insightful post on the issue: Facebook Friends, False Connection, and Social Norms. Thanks for the chat!

I knew the day would come: I’ve received my first real robot-spam on Facebook just a few minutes ago. Funnily enough, I was just this evening writing about Facebook’s slippery history with fucking over it’s core users- ever since the News Feed was introduced in the fall of 2006, followed by the site opening its doors to everyone, including third-party developers and advertisers, and of course we can’t forget Project Beacon- in my thesis.

The Spam:

Mika, a friend from high school, had been going through a “Facebook-identity crisis” over the past couple of days; each time I had logged into Facebook during this time, the “Recently Updated” tab indicated that Mika had changed several elements of his profile. Often, his changes would include a reference to the Facebook medium itself. At one point, his profile was exceedingly honest and somewhat vulnerable, his “About Me” declaring himself to be a “nice, open-minded guy,” inviting others to talk to him and get to know him more. However, this brief display of stark honesty was quickly deleted, to be replaced by a more minimal, utilitarian profile.

Curious, I sent him an IM (instant message) and struck up a conversation. Though he admitted to occasionally “giving Facebook a shot,” in assessing these attempts at honest self-portrayal he put himself in the position of someone else viewing his profile and came to the conclusion that “I would think I’m a loser.” He noted the inadequacy of Facebook profiles for truly getting to know others, particularly those he had recently met but had yet to develop a good friendship with, and expressed his desire to be able to connect “directly to people’s brains.”

His observations, spurred by his experiences with Facebook, can be applied to virtually every medium of human communication- beginning with language itself. As the early 20th-century philosopher-poet T.E. Hulme puts it: “Language is by its very nature a communal thing; that is, it expresses never the exact thing but a compromise—that which is common to you, me, and everybody.” From face-to-face conversations to modern technologies of communication, our experiences of the world are mediated by language. Through language, humans develop mutually understood symbols by which we define ourselves, our worldviews, and reality itself.

The struggle to effectively communicate one’s “true” self is not particular to online social networking; rather, the tension between one’s inner sense of self and outward portrayal of that self had been a subject of concern in Western culture long before the advent of the Internet. From the dawn of recorded language, Plato spoke of the “great stage of human life.” If, as Shakespeare mused, “All the world is a stage, and all the men and women merely players,” then what happens when the curtains close and we go backstage? In The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Erving Goffman (1956) elaborated upon this dramaturgical approach in crafting a sociological theory that has come to be known as “symbolic interactionism.” Once backstage, “the impression fostered by the presentation is knowingly contradicted as a matter of course (112).” From the symbolic interactionist perspective, one performs a certain role on the public stage that is often subverted in the private sphere (“backstage” . This private sphere allows for a more “truthful” performance of self, but is nevertheless still a performance tailored to a specific audience. The question then becomes: may one understand the “true self” when no audience is present? . This private sphere allows for a more “truthful” performance of self, but is nevertheless still a performance tailored to a specific audience. The question then becomes: may one understand the “true self” when no audience is present?

Paul Ricoeur, an eminent scholar in the field of hermeneutics and phenomenology, challenges the notion that the self is transparent to itself. Rather, he theorizes that the hermeneutic self is revealed to that self through the ‘other’- immediately and directly through two interlocuters. Furthermore, this face-to-face, intersubjective encounter is a relation that is “invariably intertwined with various long intersubjective relations, mediated by various social institutions, groups, nations and cultural traditions (Kearney 2004: 4).” One continually attempts to define the self as an individual with a unique “personality,” however this process is itself co-constructed through one’s everyday interactions with others as well as the subjective appropriation of various cultural markers of identity. From this perspective, online social networks mirror the process by which individuals construct their identities by extending interpersonal communication and providing fields in which they may articulate their cultural tastes and group affiliations.

Despite the evidence that all experiences are mediated and that the “self” is co-constructed, I have time and again encountered the pervasive belief that experiences with online social networking diminish the quality of interpersonal communication and fail to accurately portray one’s identity. This perceived disconnect may be attributed to a number of factors.

Firstly, computer-mediated communication reduces the kind of social cues we frequently rely on in face-to-face communication (such as gesture and intonation), thereby increasing the likelihood for miscommunication.

Secondly, effective computer-mediated communication demands not only literacy and the ability to effectively communicate through written text, but also a certain level of “fluency” with the specific language of the online environment in which one is participating.

Thirdly, popular online social networks pose the threat of enmeshing myriad social contexts, effectively challenging the distinctions between public and private. In these cases, the protective boundaries between the various roles we perform “onstage” and those we perform “backstage” become dangerously blurred.

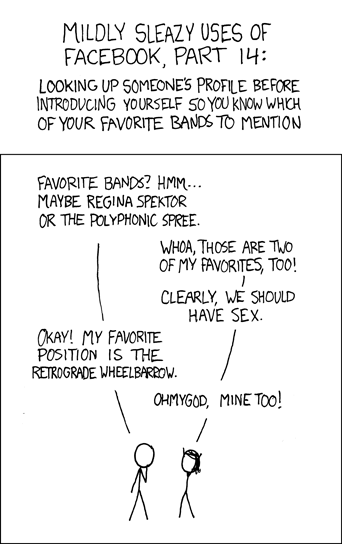

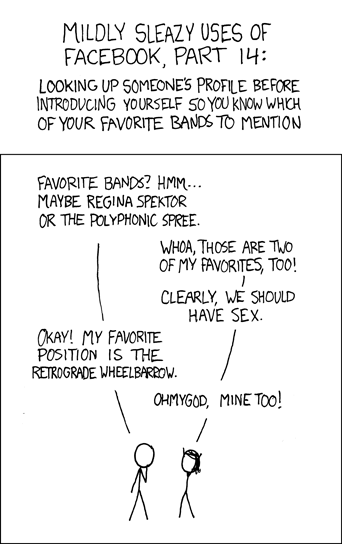

Finally, because these audiences are often invisible, we may come to know more about another through their online personas than through “natural” face-to-face interactions, and vice versa. In such cases, the “self” is projected rather than co-constructed, substantially altering the process through which we come to know another. The awkwardness of this new social phenomenon is humorously portrayed in a comic I recently came across:

Yesterday, the Facebook team announced their plan to help users battle “application spam,” describing recently-added features they’ve added that many of you should find pretty appealing. It’s a good thing, because the bevy of e-mails and invitations I’ve received in the past few months has been a real turn-off for the vast majority of “veteran” users. High school students and MySpace converts enthusiastically SuperPoke one another, adorn each others’ profiles with “Graffiti,” and rank the “Hotties” amongst their Friends (capitalized because Friendship on online social networks is quite distinct from friendship). Other Internet enthusiasts and thinkers promote charitable organizations, ask Questions of their profiles’ visitors, and incorporate their various online presences (on MySpace, SecondLife, Twitter, etc . However, those who’ve been with Facebook since the beginning (older college students and recent alumni) have a very different relationship with the site. Sure, we may SuperPoke and turn you into a vampire every once and awhile, but for the most part, Facebook serves to keep in touch with college friends scattered across the globe, see what’s come of our high school classmates, take nostalgic journeys through the hundreds of pictures tagged with our names (de-tagging when appropriate), and keep our various networks of old friends informed about our post-college lives. . However, those who’ve been with Facebook since the beginning (older college students and recent alumni) have a very different relationship with the site. Sure, we may SuperPoke and turn you into a vampire every once and awhile, but for the most part, Facebook serves to keep in touch with college friends scattered across the globe, see what’s come of our high school classmates, take nostalgic journeys through the hundreds of pictures tagged with our names (de-tagging when appropriate), and keep our various networks of old friends informed about our post-college lives.

When Facebook began allowing anyone and everyone to join the site back in 2006 and added the News Feed, thousands of college students virulently protested: some quit the site completely, many joined Facebook Groups protesting the move, and practically everyone I know complained. In response, Facebook added a slew of privacy features, such as Limited Profiles (which I use liberally) and News Feed controls. With the advent of Applications, a similar wave of protest made itself evident through such groups as “fuck off… i don’t want to be a pirate/vampire/werewolf/zombie.” Nevertheless, the number of Application exponentially increased, growing increasingly manipulative and tricksy. Many applications, particularly quizzes, practically force users to invite friends in order to see their results, resulting in the rise of groups protesting viral applications. Once again, Facebook has responded.

Here’s a run-down of the new ways you can control your “Application-Spam:”

1. Block Applications instantly. Now, when you get an invitation for the latest useless, viral Application, you can check “Block Application” directly within the invite. Nevermore, you vampires and zombies! Go bite someone who cares!

2. Clear all “Requests.” I’m not the only one who simply ignores every invitation sent my way, allowing them to build up steadily on my homepage (currently, I have 64 pending invitations). Why spend the energy rejecting every single invitation? You can be sure I’ll be clicking the “Ignore All” button (located on the “Requests” page, at the top) as soon as I finish this post.

3. Applications must now inform you ahead of time if you’re obligated to invite Friends in order to get information or access content. It’s so very irritating to spend 15 minutes filling out a quiz, only to be told afterwards that you must invite Friends to see your results. Sneaky Applications are no longer allowed to do this.

4. Forcing users to send Invitations is no longer allowed. Did you install an Application, only to find yourself forced to send invitations to your Friends in order to use it? Report it by clicking “This Application is forcing me to invite friends.”

5. Opt-out of e-mail sent by Applications. New Requests will automatically present you with this option, and you can control e-mail sent by Applicatios you’ve already installed by going to the “Edit Applications” page.

6. Help Facebook weed out the garbage from the good stuff. Getting a lot of e-mails from one of your Applications? Mark it as spam, and Facebook will take note. Did an Application break the rule I mentioned in #3? Go to the App’s “About” page and report it to Facebook.

Though it took them awhile to get around to it, I must commend Facebook on once again listening to their users and providing tools for protection against this latest version of viral marketing. Now to spread the news and help empower you Facebookers out there!

For those of you who think “Facebook Activism” is only good for whining about the company’s latest invasions of your privacy, or expressing support for Stephen Colbert’s “presidential race,” check it:

Over 270,000 Facebook members, mostly Central American youths, have joined a group called “One Million Voices Against FARC,” which was established one month ago. The group leaders organized a rally, using Facebook as a means to gather support both within Columbia as well as globally. This past Monday, between 500,000 and 2 million Columbians marched in the streets, with thousands joining them in over 133 countries worldwide.

FARC, which in English stands for the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Columbia-People’s Army, considers itself to be a guerilla movement for Columbian communism. Most of the rest of the world, including Columbia, prefers the term “terrorist organization”. The movement is specifically geared toward halting the ubiquitous kidnapping tactics employed by FARC, claiming that thousands have been wrongly imprisoned by the group for over a decade.

Nevertheless, some Columbians feel that the movement may serve only to polarize the country. Though they acknowledge the importance of standing up to unethical practices such as kidnapping, protesting FARC itself is a bit more nuanced. From The Christian Science Monitor:

“While few Colombians support the Marxist insurgent army that has been fighting the Colombian state for more than 40 years, many people are uncomfortable with the message of Monday’s rally. They would prefer a broader slogan against kidnapping and in favor of peace and of negotiations between the government and the rebels to exchange hostages for jailed rebels. The leftist Polo Democratico Party said it will hold a rally in Bogotá in favor of a negotiation but would not march. Some senators say they will march against Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, and other participants say they will be marching in favor of Colombian President Alvaro Uribe.”

The group’s discussion board is probably the best insight into the myriad issues and sentiments the struggle evokes amongst Central and South American youth, reflecting struggles against racism, classism, and corrupt governments. Thanks to Claire-bear for keeping her finger on the pulse of Free Speech Radio!

|

|

. This private sphere allows for a more “truthful” performance of self, but is nevertheless still a performance tailored to a specific audience. The question then becomes: may one understand the “true self” when no audience is present?

. This private sphere allows for a more “truthful” performance of self, but is nevertheless still a performance tailored to a specific audience. The question then becomes: may one understand the “true self” when no audience is present?