A sample text widget

Etiam pulvinar consectetur dolor sed malesuada. Ut convallis

euismod dolor nec pretium. Nunc ut tristique massa.

Nam sodales mi vitae dolor ullamcorper et vulputate enim accumsan.

Morbi orci magna, tincidunt vitae molestie nec, molestie at mi. Nulla nulla lorem,

suscipit in posuere in, interdum non magna.

|

The following was initially a comment on danah boyd’s recent post discussing Facebook’s “slippery slope” of betraying its users, most recently with Project Beacon. Please share your thoughts if you have them!

“Trusting Facebook users” are generally older folk- I think they’re more open to publicizing their online profiles because they’re seeking to make connections, they’re gaining from the public exposure and excited by all the novel possibilities. My ethnography of social networking sites primarily re/presents the voices of college students- particularly veteran Facebook users. The site started out as being a great little niche environment, so people could exchange intimate messages and upload photos from that crazy party where everyone was on a ton of drugs and so on. Then it opened up, everyone was pissed, and that’s when attitudes toward Facebook started to shift.

Most first-generation Facebookers have some degree of distrust/disgust for the site, often a great deal of it. Yet they continue to use it because it’s become so firmly integrated into campus social life- it’s a way to easily invite people to parties and share photos from said parties, to visually organize one’s social network and keep track of alumni and old high school buddies, to find out the sexuality or relationship status of that boy you’ve been admiring from afar. It’s crucial. If you’re not on Facebook, you’re going to be somewhat out of the loop.

Such important social practices generally take precedence over the egregious invasions of privacy that most are highly suspicious of. The trend is not abandoning Facebook- it’s far too useful. However, the site’s reputation is definitely tainted, and some Facebookers are using the site to form or join groups that promote awareness of Facebook’s privacy policies and petition for change. Most, however, are simply becoming more savvy and protective of their online personas; it’s become increasingly common for me to be unable to access the profiles of those I’m not friends with because of that practice. Others have simply taken to deleting much of their profiles, leaving just an e-mail address, a witty or ironic comment, and maybe a funny picture. There’s also a huge trend to apathetically accept that nothing can be done about it, much like how a lot of young people feel about our government.

Again, these are just observations of the changing attitudes among a specific subset of Facebook users. They know what’s going on (though I would say that only the Tech-savvy blog-readers have even heard about Project Beacon- but they know their information is being used for capitalist endeavors), they’re disgruntled that so much of what they do on Facebook is publicly broadcast and forever archived. Regardless of how they talk about it, however, they’re still using it regularly for everyday social practices. For many, it’s become as habitual to check Facebook as it is to check e-mail.

The character of mass media has been shifting dramatically over the past century- from the one-directional consumption of television, to the dialogical (yet niche) nature of online bulletin boards, to the enormous multimedia production of today. As the tools of new media increase in accessibility and expand in ubiquity, we find ourselves in conversation with a public audience that is more or less evident.

Knowing who one’s audience is can be a tricky process. Blogs, websites, and publicly-accessible online profiles entail invisible publics. The creation of Friend Lists and the implementation of privacy features restricts one’s audience and enhances awareness of it. Through the lens of the social graph, we can create categorical definitions of our audiences by labeling clusters of relations.

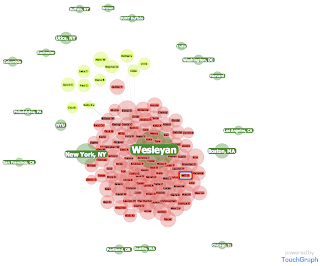

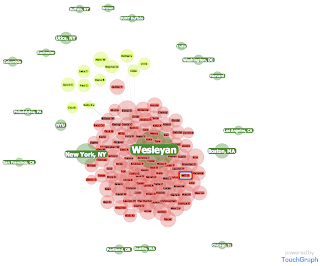

(From the looks of it, it would appear that my social network revolves around the following sites: Wesleyan, Boston, NY, San Francisco, Washington D.C, and the Northwest US):

There is something intrinsically satisfying in visual representation that text lacks. There are also few things more desirable than that which reflects oneself, however iconically.

TouchGraph, the company behind this Facebook application, says on their website:

“Traditional search engines provide a way to sift through this data. However, the greatest insights can be achieved not by sifting, but by looking at the big picture to see how items are connected.”

Just the name of the company- TouchGraph, beckons us outside of the textuality of the Internet (a quality that is becoming progressively less prominent), allowing us to grasp our wider place in the virtual world on a more intuitive level.

Such data also allows us to understand exactly how limited our individual, direct scope actually is. I predict that the practice of mirroring real-life social networks will soon become secondary to the process of producing engaging media- which, as the Internet becomes increasingly searchable, will find its place amongst wider taste fabrics. These “taste fabrics” are constructed through “word of mouth” reconfigured to the modern sense- that is, hyperlinked. In turn we may find ourselves navigating visual representations of the taste fabrics we create through our Google searches, our social networks, and our own content.

Emancipation from the material bases of inverted truth this is what the self-emancipation of our epoch consists of. This “historical mission of installing truth in the world” cannot be accomplished either by the isolated individual, or by the atomized crowd subjected to manipulation, but now as ever by the class which is able to effect the dissolution of all classes by bringing all power into the dealienating form of realized democracy, the Council, in which practical theory controls itself and sees its own action. This is possible only where individuals are “directly linked to universal history”; only where dialogue arms itself to make its own conditions victorious.

-Guy Debord

For the past two years or so, I’ve been conducting field research on online social networks (MySpace, Facebook, and Tribe.net in particular), and am now in the midst of writing up my ethnography/thesis (tentatively titled “Webnography: An Ethnography of Online Social Networks” . Hopefully, by May I will be once again walking to a podium, this time to receive my master’s degree in anthropology from Wesleyan University. . Hopefully, by May I will be once again walking to a podium, this time to receive my master’s degree in anthropology from Wesleyan University.

Cyberanthropology, as it’s often called, is a relatively new field. Nevertheless, I’m entirely overwhelmed by the vast amount of information and research available online. For those interested in the field, I’ve put together a fairly well-organized assortment of links to past studies, pertinent blogs, and must-read books on the subject. You can get to it by clicking here.

I chose to conduct my research in an area of human life that I felt I was already a part of. I’ve little desire to study the “exotic other,” as I believe true knowledge starts with an intrinsic understanding, which is then expanded through conversations with others, situating the topic within the broader context of history and philosophy, and engaging in dialogue with other researchers of the subject. While there are empirical studies out there, my own research is anything but. The only true claim to authority I have is over my own experiences.

“Language is a virus from outer space.”

-William Burroughs

In the words of Marshall McLuhan, “the medium is the message”. In other words, we’re not really saying anything new – how could we? What is changing, however, are the tools for communication. Each new medium takes on qualities of those which came before it, and extend our possibilities for communication. Thus, in the case of communication on the Internet, we experience the permanence and distantiation from time and space that print media has allotted for, as well as the immediacy and convenience afforded to us by the telephone. We are furthermore enabled to broadcast ourselves in a way that television could never quite encompass, even with “reality” programming. Unlike any previous private communications medium, our experiences on the Internet are enhanced by images, video, and sound.

“Technology is the campfire around which we tell our stories.”

-Laurie Anderson

Perhaps the greatest danger to writing about the Internet is that of technological determinism- the belief that technology determines changes in society. On the contrary, societies develop technologies that are always being shaped by the culture they’re embedded in. We are not a society being altered through our technologies- rather, we are human beings engaging in the same activities through the use of evolving tools (hence the “campfire” metaphor, above). The modern age, however, has arguably transformed humankind’s way of thinking and perceiving in ways that have yet to be fully determined. Understanding where we are, where we’ve come from, and where we are going is an important endeavor, I believe, if we are to understand the implications of modernization and the future of this planet.

As the tech world continues to grow wild for Facebook, the veteran users in my midst- college students- continue to grow indifferent, even annoyed- or so their group discourse would have me believe. “The applications were pretty fun at first,” said one energetic, people-loving friend, “I like throwing food at my friends and turning them into zombies… but it got old real fast.” “They’re stupid, they’re annoying, I just really don’t care at all anymore,” said another friend, who’d spent his past semester abroad, “I mean, I guess it’s useful for keeping in touch with people you don’t care enough about to e-mail.”

“Well, I care so little that I let her,” Dave points a finger at his girlfriend, “go in and change my whole profile around. It’s ridiculous, and I haven’t even changed it back.” They giggle for awhile.

“There are some useful applications,” I point out.

“Well, there’re so many of them, I don’t feel like sifting through all of that crap. Facebook’s turning into MySpace.”

At the same time, I’ve found that my friends on Facebook continue to be highly active, having become skilled at interacting with the more useful features of the site. 25% of the most recent 50 emails in my inbox are Facebook notifications of some sort- generally, event listings, friend requests, wall messages, and pokes. These are some of the ways in which we attempt to connect to one another through forming and maintaining relationships and collective cohesion, digitally.

My conclusion? It’s just not “cool” to like Facebook- one is better off being critical- but many of us depend on it in some way or another as a way of maintaining social bonds. We’ve grown addicted.

|

|

. Hopefully, by May I will be once again walking to a podium, this time to receive my master’s degree in anthropology from Wesleyan University.

. Hopefully, by May I will be once again walking to a podium, this time to receive my master’s degree in anthropology from Wesleyan University.