|

|

A recent post on ReadWriteWeb discusses the general decline of the popularity of print media and the shift toward reading activity conducted primarily online. We are in the midst of transitioning to yet another form of media, and, like television before it, many of the concerns about this shift pertain to whether this medium is good or bad for “society.” I would argue that the imposition of a value structure in understanding the changes this shift has been accompanied by is insufficient.

While newspapers played a significant role in the formation of national consciousness (through an awareness of an increasingly shared readership), television and the music industry brought people together on the basis of shared cultural tastes that helped individuals to define themselves through identifying with specific niche interests. The Internet has helped to extend this process of individualization, and in the process has transformed the degree of agency people have in learning about the wider world, and most importantly, granting them a voice with which they might be part of that world.

The information we “digital natives” now come across on the Internet is increasingly social in nature. As opposed to the more “top-down” distribution of news and entertainment, the social web creates a heightened sense of shared readership by creating a more horizontal structure (think Digg, social networks, the blogosphere, etc . As a result, we are given more agency in assessing the quality of information – leading to a new form of reading that involves scanning, filtering, aggregating and organizing. I would argue that this is not a “dumbing down” at all, but rather a qualitative shift in the way we learn through media. The question then becomes, who is in fact “dumber”- the person who reads the newspaper that lands on her doorstep and accepts it as the truth, or the person who reads bits and pieces from many news sources (including blogs) and is able to piece together a more complex perspective? . As a result, we are given more agency in assessing the quality of information – leading to a new form of reading that involves scanning, filtering, aggregating and organizing. I would argue that this is not a “dumbing down” at all, but rather a qualitative shift in the way we learn through media. The question then becomes, who is in fact “dumber”- the person who reads the newspaper that lands on her doorstep and accepts it as the truth, or the person who reads bits and pieces from many news sources (including blogs) and is able to piece together a more complex perspective?

I think a more pertinent question to ask is the degree to which the Internet is affecting individual or collective identity- the concept of “networked individualism,” introduced by Boase and Wellman, suggests we are expanding our social networks (weak ties in particular) according to our individual interests and communities of membership, thus diversifying the kinds of information available to us. Simultaneously, through the Internet we are potentially approaching the fulfillment of McLuhan’s notion of “the global village,” and in the process forming a new sort of collective identity- the feeling that we are not only a part of, but increasingly connected to the world on a global scale.

Several months ago, someone told me about social networking sites that function as matchmaking tools for arranging marriages- a cultural practice that is common for nearly half the world’s population, including India, China, and Indonesia, as well as Hindus, Muslims, and Buddhists. In a fit of brainstorming for my next research project, this conversation came to mind and I quickly discovered Shaadi.com, an Indian version of an online dating site. Curious, I filled out a profile of my own to see what kinds of categories one could choose amongst for self-representation.

Well, first of all, it’s clear that most of the profiles on the site are filled out by parents, who are traditionally responsible for the search for and approval of potential husbands and wives. Among the more salient identity markers are Religion/Community (Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Jain, Parsi, Buddhist, Jewish, “No Religion,” “Spiritual- Not Religious,” and “Other), Education, Profession, and Lifestyle (diet, smoking and drinking habits). Arranged-Marriages are ideally between two members of the same caste or sect, and Shaadi.com certainly covers the gamut. Potential matches are also frequently judged by education level and profession, as well as the aforementioned “lifestyle habits,” which are heavily informed by religious beliefs.

A few other things I learned about while creating a profile on the site:

• The alignment of the stars at one’s birth determines if a person is a Manglik, and Shaadi.com inquires as to one is. In Indian astrology, Mangliks are destined for difficulties in marriage. In order to balance out these negative forces, it is often suggested that a Manglik marry another Manglik, based on the idea that two negatives make a positive. Astrology in general is quite important for many Indians, especially Hindus, when it comes to marriage, and Shaadi.com users may incorporate a variety of astrological readings in their profiles.

• Like pretty much every social networking site, one can fill in an open-ended “About Me” box. However, on this site, there is also a significant section called “About My Family.” Shaadi.com offers a few pointers for users filling out this section, the first of which suggests describing the family’s outlook and approach towards life. Early on in the registration process, one could select whether her “Family Values” are traditional, moderate, or liberal. Clearly, the degree to which one’s family embraces more traditional or more liberal attitudes and values has a significant effect on the matrimonial process.

• Admirably, the site also inquires about users’ HIV status. Though figures place the percentage of HIV-infected people in India at a seemingly minute 0.36%, with the country’s enormous population this amounts to between 2 million and 3.6 million Indians living with HIV. While there is some evidence that the rate of infection is currently declining, likely due to successful prevention and awareness campaigns, there is also plenty of evidence to the contrary. Given the rampant fear and stigmatization of HIV-positive individuals in communities everywhere, marking oneself as HIV-positive on the site likely drastically reduces one’s chances at finding a spouse. However, as with both Mangliks and “Special Cases,” another profile category wherein one can indicate mental and/or physical handicaps, the site makes finding others who share their “condition” a much easier process in many ways.

This semester, I am taking only one class as I complete my graduate thesis, the last class I will ever take at Wesleyan: Nationalism and the Politics of Gender and Sexuality with Professor Kauanui. Like most of the classes I’ve taken, I’m to conduct a semester-long research project, giving me the opportunity to conduct another mini-ethnography related to online social networking. As such, I’ll be regularly posting my most pertinent and interesting findings. Stay tuned!

To date, little to no research has been published on the growing trend of arranging marriages using online matrimonial services. However, I was able to find a small body of contemporary literature concerning online romance more generally. Online courtship, like traditional arranged marriage, is a process by which two people come to know one another before their romantic love develops, if it does indeed develop. Online matchmaking services and social networking sites (such as MySpace) enable individuals to learn about potential mates before even initiating conversation, let alone meeting them face-to-face. A common criticism of Western courtship practices is that such relationships often become sexual before two people really get to know one another, and thus the passion of initial lust is frequently mistaken for love. In framing these criticisms, the high divorce rate in the US is often cited as evidence that “love marriages” are not all they’re cracked up to be:

“Arranged marriages have worked well in the past. But like I said earlier, love doesn’t necessarily last. In America the divorce rate is over 50%. I think the whole myth of instability in arranged marriages is blown out of proportion. More often than not, it’s the love marriages that end up in ruin.” (Indian High School student on Facebook India network forum, Nov. 2007)

It is important to assess the social consequences of new technologies, particularly those that may at once challenge and reinforce traditional practices and beliefs in conflicting ways. My preliminary findings reveal that online matrimonial sites empower young Indians and Indian Americans by: expanding the field of potential marriage partners; granting them a greater degree of autonomy in choosing them; and facilitating the search process, thus making it easier to find others compatible with one’s upbringing, lifestyle, personal goals, and beliefs. At the same time, many seem to view their membership on the site as either a current duty or a future inevitability, yet another obligation fulfilled in order to appease the demanding high expectations of Indian parents. The frustrations experienced by young Indian Americans in relation to the expectations of their parents is exemplified by the popular Facebook group “I can’t live my life the way I want too because I got DESI PARENTS!” which has 3,802 members. The mass appeal of Shaadi.com may, I suggest, lie in its successful fulfillment of both the young modern Indian’s drive for independence and autonomy, as well as the older generation’s inherited traditions of ensuring compatibility between their children in accordance with specific markers of identity.

Indian Americans, in particular, struggle to formulate self- and collective identities that fulfill the often contradictory demands of traditional Indian values and modern American ambitions. The result is a variety of hybridized identities collectively known as “desi.” The identity crisis faced by the children of India-born “desis” living in the Western world has given rise to the term “ABCD,” or “American-Born Confused Desi.” The situation of Indians in the 21st century is one marked by extensive transmigration, evolving communications technologies and subsequent increased career possibilities for both men and women, and the influx of Westernized ideals of self-determination and independence. There are complex forces at work here, and any sensitive exploration of these issues would do well to avoid framing them as merely binary oppositions (ie; traditionalism vs. modernism, Indian vs. Indian American). Rather, I intend to conduct original research, exploring the complex experiences of individuals encountered “in the field” through discursive analysis and participant-observation. These include native Indians as well as American-born Indians, and the various unique ways in which these individuals incorporate different Western and Indian values in the construction of their worldviews, sense of belonging in their communities, and production of self-identities in talking about marriage and engaging with Shaadi.com. In particular, understanding and articulating the plight of Indian and Indian American women, who must balance traditional norms of self-sacrifice to the family with their own desire for independence, may shed light on similar struggles faced by women around the world.

This past month, I’ve sought to nourish myself through what is, for me, the most difficult period of the year. January. And I made it! I’m okay! And I’ve written a lot of things.

In fact, I was recently hired to join a team of bloggers, helping to create the “meat” of a pre-beta social networking site, iggli. You can check out my blog here, or by clicking on the title of this post. It’s where I’ve been writing regularly these days. Original writing, at that.

Having shaken myself free from the noxious syndrome of reading “research” and creating headers beneath which I can conveniently categorize the perspectives of others into “anxieties” and “utopias”, I have now reached what will be the butter on the bread of my thesis. That is, that which makes the dry foundation delicious. Not that ethnography is ever dry. My first chapters are rife with the stories, anecdotes, personalities, ideas that propelled me to do this research in the first place.

But now, allow me to be indulgent. I embark on a chapter I’ve hesitantly entitled “A Phenomenological Exploration of Online Social Networking.” This is where I tell my own story, where I deeply investigate my own integration of anxieties toward and utopic visions of the Internet and its potentials and failures.

And everything else.

The past week has consisted of moving into a new apartment (where I will no longer bother touchy neighbors with my entirely nocturnal rhythm and proclivity toward human interaction and [god forbid!] music), sleeping 10-12 hours a night, and battling the obvious onset of ill health with my finest vegetarian cooking, isolation, and relaxation.

I sit before the screen now resolved to put forth a testimony founded on inner truths, desires, sadnesses, attempts to bridge the increasing divide I see between individuals and community. The Internet, for me, is the “final frontier” in which we may remake ourselves, and in so doing, contribute to the remaking of this severely damaged world.

Though, as severely damaged as it is, it is because of my overwhelming love of the stories, personalities, and lives of others that I have become so enamored with the potential for anthropological research to promote human understanding, empathy, and that elusive yet all-empowering ultimate pursuit: community, connection, the sense of belonging and the extension of selfhood.

This has been a manifesto.

Mika, a friend from high school, had been going through a “Facebook-identity crisis” over the past couple of days; each time I had logged into Facebook during this time, the “Recently Updated” tab indicated that Mika had changed several elements of his profile. Often, his changes would include a reference to the Facebook medium itself. At one point, his profile was exceedingly honest and somewhat vulnerable, his “About Me” declaring himself to be a “nice, open-minded guy,” inviting others to talk to him and get to know him more. However, this brief display of stark honesty was quickly deleted, to be replaced by a more minimal, utilitarian profile.

Curious, I sent him an IM (instant message) and struck up a conversation. Though he admitted to occasionally “giving Facebook a shot,” in assessing these attempts at honest self-portrayal he put himself in the position of someone else viewing his profile and came to the conclusion that “I would think I’m a loser.” He noted the inadequacy of Facebook profiles for truly getting to know others, particularly those he had recently met but had yet to develop a good friendship with, and expressed his desire to be able to connect “directly to people’s brains.”

His observations, spurred by his experiences with Facebook, can be applied to virtually every medium of human communication- beginning with language itself. As the early 20th-century philosopher-poet T.E. Hulme puts it: “Language is by its very nature a communal thing; that is, it expresses never the exact thing but a compromise—that which is common to you, me, and everybody.” From face-to-face conversations to modern technologies of communication, our experiences of the world are mediated by language. Through language, humans develop mutually understood symbols by which we define ourselves, our worldviews, and reality itself.

The struggle to effectively communicate one’s “true” self is not particular to online social networking; rather, the tension between one’s inner sense of self and outward portrayal of that self had been a subject of concern in Western culture long before the advent of the Internet. From the dawn of recorded language, Plato spoke of the “great stage of human life.” If, as Shakespeare mused, “All the world is a stage, and all the men and women merely players,” then what happens when the curtains close and we go backstage? In The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Erving Goffman (1956) elaborated upon this dramaturgical approach in crafting a sociological theory that has come to be known as “symbolic interactionism.” Once backstage, “the impression fostered by the presentation is knowingly contradicted as a matter of course (112).” From the symbolic interactionist perspective, one performs a certain role on the public stage that is often subverted in the private sphere (“backstage” . This private sphere allows for a more “truthful” performance of self, but is nevertheless still a performance tailored to a specific audience. The question then becomes: may one understand the “true self” when no audience is present? . This private sphere allows for a more “truthful” performance of self, but is nevertheless still a performance tailored to a specific audience. The question then becomes: may one understand the “true self” when no audience is present?

Paul Ricoeur, an eminent scholar in the field of hermeneutics and phenomenology, challenges the notion that the self is transparent to itself. Rather, he theorizes that the hermeneutic self is revealed to that self through the ‘other’- immediately and directly through two interlocuters. Furthermore, this face-to-face, intersubjective encounter is a relation that is “invariably intertwined with various long intersubjective relations, mediated by various social institutions, groups, nations and cultural traditions (Kearney 2004: 4).” One continually attempts to define the self as an individual with a unique “personality,” however this process is itself co-constructed through one’s everyday interactions with others as well as the subjective appropriation of various cultural markers of identity. From this perspective, online social networks mirror the process by which individuals construct their identities by extending interpersonal communication and providing fields in which they may articulate their cultural tastes and group affiliations.

Despite the evidence that all experiences are mediated and that the “self” is co-constructed, I have time and again encountered the pervasive belief that experiences with online social networking diminish the quality of interpersonal communication and fail to accurately portray one’s identity. This perceived disconnect may be attributed to a number of factors.

Firstly, computer-mediated communication reduces the kind of social cues we frequently rely on in face-to-face communication (such as gesture and intonation), thereby increasing the likelihood for miscommunication.

Secondly, effective computer-mediated communication demands not only literacy and the ability to effectively communicate through written text, but also a certain level of “fluency” with the specific language of the online environment in which one is participating.

Thirdly, popular online social networks pose the threat of enmeshing myriad social contexts, effectively challenging the distinctions between public and private. In these cases, the protective boundaries between the various roles we perform “onstage” and those we perform “backstage” become dangerously blurred.

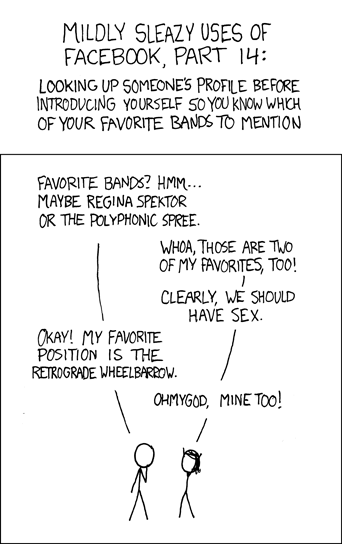

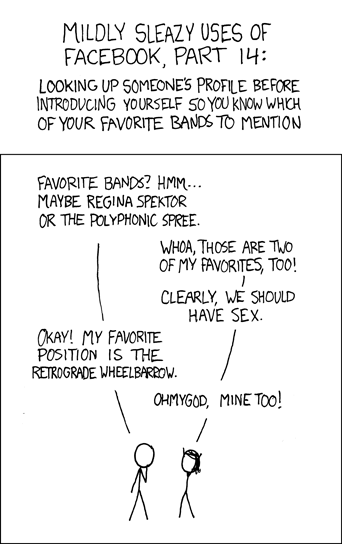

Finally, because these audiences are often invisible, we may come to know more about another through their online personas than through “natural” face-to-face interactions, and vice versa. In such cases, the “self” is projected rather than co-constructed, substantially altering the process through which we come to know another. The awkwardness of this new social phenomenon is humorously portrayed in a comic I recently came across:

|

|

. As a result, we are given more agency in assessing the quality of information – leading to a new form of reading that involves scanning, filtering, aggregating and organizing. I would argue that this is not a “dumbing down” at all, but rather a qualitative shift in the way we learn through media. The question then becomes, who is in fact “dumber”- the person who reads the newspaper that lands on her doorstep and accepts it as the truth, or the person who reads bits and pieces from many news sources (including blogs) and is able to piece together a more complex perspective?

. As a result, we are given more agency in assessing the quality of information – leading to a new form of reading that involves scanning, filtering, aggregating and organizing. I would argue that this is not a “dumbing down” at all, but rather a qualitative shift in the way we learn through media. The question then becomes, who is in fact “dumber”- the person who reads the newspaper that lands on her doorstep and accepts it as the truth, or the person who reads bits and pieces from many news sources (including blogs) and is able to piece together a more complex perspective?